[Found these pages in 2014; posting them now.]

Notes from Underground, or Wherever

by Marcus Heath

November 12, 2008

So I died. I know, not what I intended. But it happens. It’s really frustrating, because there were all these things that I wanted to say to people, and now I can’t.

You’d think I could just wait until they get here, and tell them then. But I’m not sure it works that way. I’m in solitary confinement. The only living thing I’ve seen since I got here is Max, a therapist who stopped in briefly. No windows. It seems like I woke up in this cell, and that’s where I’ve been ever since. I asked Max how long I’m here for, and what comes next. He just shrugged. He may be a good listener, but he’s not much for conversation.

I told Max there were all these things I wanted to say. He suggested I write them down. He got me some paper and a couple of pens and said he’d check back. Not sure how long ago that was. It feels like it’s been a while.

Chapter 1

God and His Mercy

My cell seemed to be all concrete. No windows, in the door or anywhere else. No handle on the inside of the door. I went over and gave it a shove. It didn’t budge.

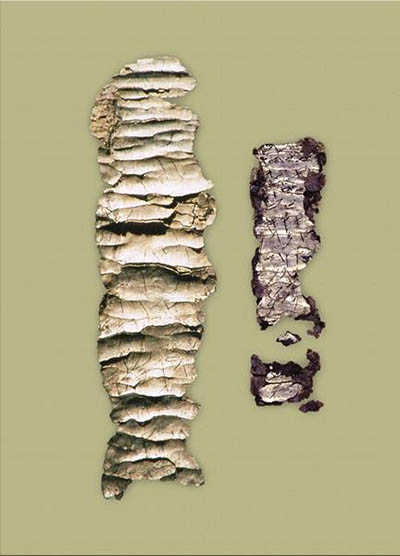

My cell didn’t have a lot in it. A bed, a table, and a Bible.

I wasn’t sure what to make of that Bible. I didn’t recall the Bible saying anything about being put in a solitary cell and visited by a therapist. Maybe that copy of the Bible was there for the particular torment of people who had wasted their lives believing it?

Some people, I knew, would take that Bible as a hint. Time to clean up your act and be holy. This has never been my style. A thousand preachers and random Bible-thumpers had told me, all through my life, how it works: you make your decision about God, you roll the dice, and you see how it turns out. No such thing as a redo after the fact. Anyway, if there was a God, he already knew me inside and out. Nobody’s fool. Which would probably explain why I was in solitary, and appeared likely to stay here.

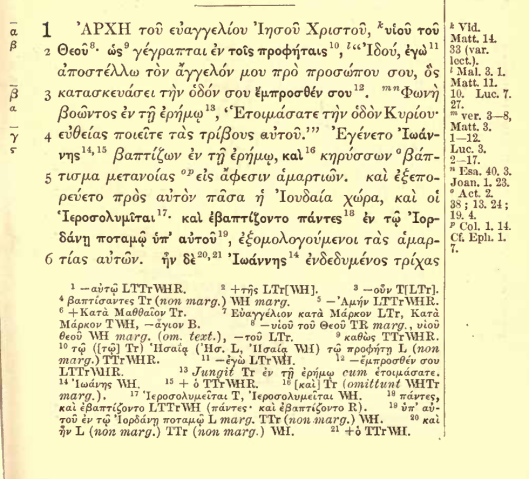

But waste not, want not. I got the idea to use that Bible as a guide for my writing. I would open it to a random place, put my finger down, and use that passage to tell me what I should write about. I flipped it open, and here’s what I got first:

Luke 6:36. Be ye therefore merciful, as your Father also is merciful.

Well, that was true. My dad was merciful. Not often, but he was. But of course Luke was referring to God, my Father in Heaven.

As I thought about it, I realized I really didn’t have a lot to say to God. Probably a bad place to start my little writing effort. For one thing, I doubted there was such a thing as the Christian God. He seemed to be an invention, like Citibank or the USSR, by people for whom there is no such thing as too big. This God, they said, could do anything! I was still waiting to see if he could create a rock so big he couldn’t lift it. He knew everything! Which meant that all his believers were just living out their lives, waiting for whatever he had already decided should come next. And it showed in their lack of creativity and zest for life.

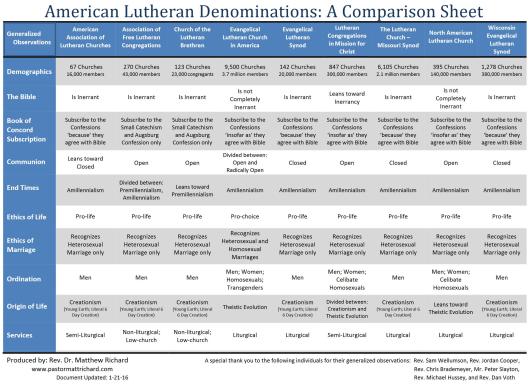

Of course, if I had believed in the Christian God, by this point I would have had endless things to complain about. How could he this, why did he that. Evil, and torture, and the deaths of children and kittens. Why doth the evil man prosper, etc. All good questions. Maybe this cell had seen others before me who had raged thus. Maybe this Bible had answered their concerns. Odd that the warden didn’t include a Koran or a Book of Mormon, but maybe they had separate cells for those types. Maybe I had a Bible because God’s sources were misinformed. Don’t tell me they were relying on the membership rolls of the Lutheran Church, in which I was confirmed after the eighth grade. Those people weren’t even speaking to me anymore. Well, they definitely weren’t, now that I was dead.

I thought about raising this with Max, next time I saw him. But not to complain. They might replace the Bible with something worse – the ravings of some religious psycho, or the Bhagavad-Gita, which I had found completely inscrutable, the one time I looked at it. Besides, I was not yet finished with this old black volume. Black, the color of death. I thought it might be nice, not only to get some mileage out of it, but also, eventually, to kiss it goodbye.

It occurred to me that, in writing these words, I had made the mistake so many people make. I had become preoccupied with the part about God, in that Bible passage, and had neglected the part about mercy.

It would be hard to agree that God is merciful if you don’t believe he exists. But I didn’t say there was no God; I just said that the Christians seem to have walmarted him. The problem with a bloated God was that he couldn’t win. When you control everything, you don’t deserve credit for doing nice things; you ought to be doing more nice things. Everything ought to be nice. We expect a congenial suburban God who will make things as comfortable across the universe as he has done for us right here in our little cul-de-sac.

It would be very refreshing to discover that God was just a god, just one more badass on the local divinity front, hanging out and maybe sometimes screwing up. In that case, being merciful would be a sign of good character; there would be other badasses who weren’t.

I did believe that God, or god, or the gods, were merciful. I’d had a good life. I’d been damn lucky in a lot of ways.

The Bible was telling me to be merciful too. I realized that I should. And, weird thing, in the moment when that occurred to me, it felt like I saw a glimmer of light straight from the first century, like candlelight through a crack into the room where Luke was writing those words. Like the programmer has broken the code: the door is opening. Nothing supernatural; it was just a little feeling. Obviously my imagination – no candles here – but a cool little head trip nonetheless.

It did appear that I might have a lot to say about God after all. But there didn’t seem to be any rush. And, after all, this was the Bible. It’s not as if this would be the last time the subject would come up.

Chapter 2

Sold Down the River

While writing the foregoing words, there in my solitary cell, it felt normal, like when I’d written things during my lifetime. I could write a paragraph and stop, and it would feel like that had taken maybe three or four minutes. But for some reason, by the time I finished that first chapter, it felt like I had been at it for a week.

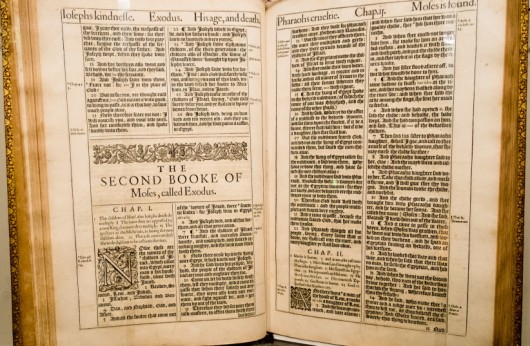

Anyway, I opened the Bible and punched my finger down onto another page, and this time, here’s what I got:

Genesis 37:31. And they took Joseph’s coat, and killed a kid of the goats, and dipped the coat in the blood.

I remembered this story. Joseph’s brothers sold him into slavery, and then used the bloody robe to make their father think he had been killed by a wild animal. And then Joseph wound up in Egypt, Pharoah’s right-hand man, rich and famous, and his brothers came in, years later, poor and desperate, and bowed down to him, not recognizing him.

This, I felt, was going to happen to me too. Or at least I used to think that, before I died. The bastards had sold me out – referring, here, to all the bastards in the world at large, and especially those whom I’d had the misfortune to meet – but I was going to hang tough, and my day would come, and they would all be sorry. It was a little embarrassing to recall those feelings now because, oops, turns out I was wrong.

I had been sold out lots of times. I vividly recalled when I innocently tried to kiss Debbie, in the first grade, and she immediately said she was going to tell the teacher. I had thought, hey, maybe we had a thing going. But no. Still, it was just in the spirit of good clean fun, right? No. Tried to persuade her that we were going to grow up and go to college someday and needed to be mature about this, but for some reason I just couldn’t talk her out of it. I don’t recall that I was punished for it. It was just the principle of the thing.

Well, and matters had gone downhill from there. Liars and suckups and backstabbers. Life was full of them. Friends who share your personal secrets with your enemies. Cheating women. Thieving corporations, always trying to steal another dollar. Like you spend your life with these cockroaches crawling all over you, and the only deliverance short of death is that eventually they feel normal.

Which moved me to pause and reflect. Suddenly it seemed there might be no more of that for me. Hard to tell what Max & Co. might have in store, if I ever got out of my cell. Maybe that would never happen; maybe I would always be here. Well, if so, it could have been worse. I would probably go insane from the solitude eventually. Couldn’t decide if that would be a bad thing. Might help me pass eternity. Especially if there would be no embarrassment to it, nobody but Max to notice. He probably would have seen it a thousand times before.

But it did seem that, while I was in here and maybe afterwards as well, there might be no more scummy parasites, waiting to feed on my body or soul. Odd to feel a sense of freedom, or of lightening my load, while being held in solitary confinement in hell, or wherever I was. But I did, suddenly, a little bit.

This line of contemplation was not helping, however, in my mission to relate what I had been wanting to say to people, during my life. I had wanted to tell those people off.

As I thought about this, I started crying. Well, not crying, exactly, but a tear came to my eye. Caught me off guard. Not sure exactly why it happened. Suddenly there was nobody left to fight with; just me and all that anger. It was, like, You guys, you should not have treated me like that. I loved you! But wait – was that true? Well, yeah, sometimes. It felt like I really had loved some of them. I had definitely wanted them in my life. I had trusted them. They had been my friends. Or pretending to be. It really hurt, now, to feel like such a loser, a fool, a joke to them.

I say I got just a tear in my eye but, truth be told, I’m not sure how much time passed in that sad state. It seemed like these moments of feeling and reflection got stretched out somehow, like what I was saying before. Somehow it felt like I was spending a lot of time sitting and thinking. I’m not sure I actually was; that’s just how it felt.

What I had wanted to do, in my life, was to get even. My turn would come, and I would feel righteous, as I stood there watching them suffer for what they had done to me. It was a natural human urge. No, a divine urge. It was exactly what the Hebrew God would have done: identify your enemies and nail them. An eye for an eye, and then some.

As I dwelled on this, it occurred to me that maybe those cockroaches, the enemies of my lifetime, would have their own turns someday, in cells like this one. Then they would be glad for the times when they had delivered payback to someone who had done them wrong, and they would feel cheated for the times when they could not get even. They would not be troubled by what they had done to me, but they would sure feel bad about what someone else had done to them.

So, yeah, they would still be scum, even after death. They would be feeling exactly what I was feeling. Served them right.

But then, that made me out to be exactly like them. Like I was one more cockroach of life. Because I knew that, out there somewhere, there were people who had wanted to pay me back, and now would never have the opportunity.

Or, shit, maybe they would. I wouldn’t be around to defend my reputation, or the people I loved. I thought about that for quite a while, going back and forth with the flood of emotions, visualizing good people being harmed, gradually calming down into the belief that, actually, it would be only the rare psychopath who would punish someone else for their anger against me. For the most part, you get your chance, you die, and then you are out of the picture, and people have someone or something else to worry about instead.

That was calming. There was a sense of finality about it, a sense that this part of the story was done. The scores were about as settled as they were ever going to be; and even if they weren’t, it seemed I wouldn’t be hearing about it. I couldn’t do any more harm, according to everything that I knew and believed about life after death, and it was possible that nobody was going to harm me anymore either. Max & Co. might have to keep me in protective custody for all eternity, here in this cell, to make sure of it. But from what I could see at present, that was how it was going to work out. I could live with that – or I guess not, but you know what I mean.

So I picked up the Bible and read the rest of the Joseph story. It wasn’t entirely clear what happened, sounded like a lot of back-and-forthing, maybe some game-playing on Joseph’s part. But in the end he didn’t punish his brothers for selling him into slavery. And that was fine with me. Now that I was dead, and couldn’t do anything about it, I decided I might as well get over the idea of getting even. Not that I actually would, but it was a nice way to think.

Chapter 3

Me

I was not sure exactly who I was, there in my cell.

My thoughts were definitely my own. I was still me. I didn’t have the sense that God or anybody else was playing with my mind, or that there was anything fake or imaginary about what was going through my head. It was weird to have the sense that I was spacing out, in my reflections, and letting minutes (or years, or whatever it was) go by. But it still felt like it was good ol’ me, experiencing that.

My physical body, if that was the right term for it, felt real too. I was definitely imprisoned. I couldn’t walk through the walls of my cell. I was breathing. I could see my pulse on my inner bicep. I didn’t try to draw blood, but it certainly looked like there was blood there to be drawn, if I found a pin or a knife.

This was problematic. I knew I had died, and I was willing to bet that my real physical body had remained there on Earth (assuming I wasn’t still on Earth myself, or inside Earth somehow). I doubted that God or whoever had done a swap, putting a fake body there for the mortician to gut and stuff with goo, or whatever morticians did.

I guessed it was possible that there was a parallel universe, and that this body I was using now had always been kept here, waiting to be inhabited with my mind. But if it had been sitting around in this alternate universe, it wouldn’t look exactly like mine. I checked: yes, there was the scar from last year’s bike accident on my right elbow. Definitely me.

To look like mine in every detail, this body would have had to go through exactly what I was going through during my life on Earth, except maybe for the final moment of death. Anything was possible, but I doubted this was the situation.

I decided the best explanation was that they kept something like an inflatable body on hand, or maybe more like a stem cell. At the moment of death, this body seed would take on the form and condition of the mind that had been inserted into it. God or his deputies had been tracking what my body was like, or maybe my own mind had mapped my body in such detail that no divine intervention was required: just insert the mind and let it tell the body seed what it’s supposed to look like.

I wondered how that would work with a little baby that died shortly after birth. I wasn’t sure about fetal development and all that. I guessed that even the newborn has a sense that it has arms or it can cry and make noise. Maybe the body seed for a dead newborn would look more like a vague puff of pink flesh. Or, hell, maybe nobody would see it except the newborn itself, here in solitary. In that case, it could look like anything at all, and nobody would know the difference.

Except Max. Max would see that blob of pink flesh. Max would see my body. But, jeez, what if the body I saw was not what Max saw? Maybe my mind had said, this is your body; this is what your body looked like, last time you checked; and therefore that’s what I would think I was seeing, when I looked at myself – but meanwhile, maybe what Max saw, when he looked at me, was a funhouse image, or a sailboat, or just another blob of pink flesh. Or a cockroach.

No telling where this was going to end up. If I did actually have the body that I seemed to have, here, then maybe I would be able to change it. Maybe I would be learning cool tricks to make myself look better or be stronger. Or maybe I would just be imagining it. No clue.

I thought to write about who I was, there in my cell, because of the next Bible passage I selected at random:

Jeremiah 33:3. Call unto me, and I will answer thee, and shew thee great and mighty things, which thou knowest not.

I had already done a bit of musing on the “me” part, referring there to God; the question at hand was, who was the “thee” (i.e., the me) to whom God was speaking? Not that I was entirely sure he had intended to be addressing me in particular. The adjacent passages seemed to suggest he was speaking to the people of Israel, and I was just this latter-day interloper who had been taught to assume that every word of the Bible was meant for me personally. Well, whatever. This was my book, and I say that Isaiah was talking directly to me, here in hell, two thousand years later. Seemed reasonable.

I couldn’t say that my body was exactly the same as before, because I hadn’t eaten a thing since arriving here in this cell, and that had been, what, weeks ago? I didn’t seem to be hungry. Hadn’t drunk anything either. I didn’t seem to need to go to the bathroom. I tried to pee a bit in the corner of my cell, as an experiment, but nothing came out.

So, OK, that was not a normal physical body. Didn’t mean my new body was fake. That might just have been how this place works. You get your sustenance from the air or something; your cells operate on some new principle. It was possible to run the same software on different kinds of hardware; maybe that was the situation here with my body and my mind.

I did miss food, especially at the beginning. Not so much as a chronological habit, telling me it was time for breakfast or lunch. I had no idea what time of day it might have been, if “day” was even a coherent concept here. What I missed was the variety of activity. You write for a while, you pace back and forth in your cell, it occurs to you that it might be nice to have some pizza and watch a movie on the tube. And then go to bed. I hadn’t slept either. Or at least I don’t think I had.

I wondered why I would still have a body that looked like it could eat and pee, if there was not actually going to be any eating, yawning, or peeing in this place. Maybe those things would be optional, if you were in the right place or state of mind, or if you really wanted to experience them. Or maybe my mind was just temporarily inhabiting this form of body: maybe God or my mind would change the body as my thoughts gradually moved away from the old familiar habits of life on Earth. Use it or lose it. Which, horrors, could have adverse implications for my penis size.

There were obviously some puzzles here. But they didn’t seem to merit much intensive speculation. Whatever the situation was, I had no doubt that the people in charge had covered their tracks. I would be able to see and learn what they wanted me to see and learn, and nothing more.

Chapter 4

The Lord’s Precepts

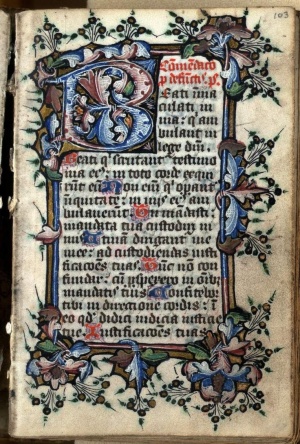

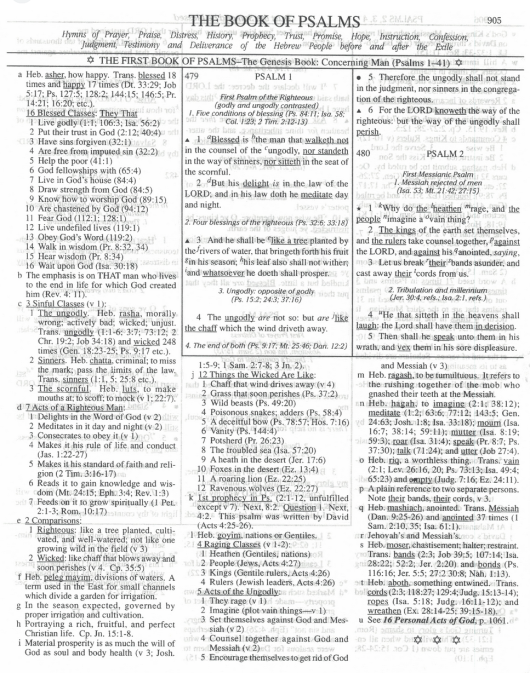

This time, when I spun the wheel and pointed to a passage in that Bible, I got something from the Psalms:

Psalm 119:93. I will never forget thy precepts, for by them thou hast preserved my life.

Verse 93, eh? This long Psalm seemed to be about law. And that was about right. It would probably take at least 93 verses to write a psalm about law and anything, including law and the Lord. Law is longwinded.

I knew a bit about law. I had once been an attorney. Then I had abandoned that abominable profession and never looked back. Ah, but the law did. It always looked back, forever backwards.

I was not going to be able to write down all of my law-related thoughts and experiences within a reasonably brief space. I would have to keep a pretty tight focus, here, on just what David had said in verse 93. (As I recalled, the traditional Christian view was that Israel’s King David had written all of the Psalms, though it also seemed to me that some people thought that some of them must have been written by someone else.)

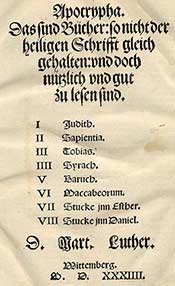

Well, on this subject of law and the Lord, I could start with the number of the verse, 93. Believe it or not, God had forgotten to supply that number. The whole Bible – he put it together, sent it out for printing, and then smacked his forehead: I completely forgot to add chapter and verse numbers! His mistake had to be corrected by anonymous scribes, somewhere along the line, so that people could argue about individual statements as lawyers would. Because this was the Lord’s will.

I didn’t recall what the ancient Hebrews used for a numbering system, but I was pretty sure it was neither Roman nor Arabic. Maybe this is why God did not bother David about it: he knew that people of some other ethnicity, hundreds of years later, would have a numbering system superior to the one possessed by his Chosen People. No point bothering David about that. He had enough on his mind, on his way to becoming the Bible’s greatest king. Screwing his best general’s wife, for instance. She was reputed to be a looker, a regular Star of David.

But what were we saying – oh, yes, that David was assuring God that he would never forget his precepts. I knew the word, “precept,” but wasn’t sure of its exact definition. Rule, I suspected. And that would be about right. David would never forget the rule against adultery, for instance. It would be right there in his mind. A bit off to the side sometimes, but never entirely forgotten.

I couldn’t tell why David would say that God’s rules had preserved his life. The previous verse said, “Unless thy law had been my delights, I should then have perished in mine affliction.” Not sure when “then” was. David probably wrote these things when he was a young man, lurking by a stream with his lute, or mandolin, or whatever musical instrument he happened to play. His teacher in Hebrew school was probably encouraging him to take pleasure in the limited set of Jewish scriptures available at that time. Back then, they didn’t have movies. They weren’t waiting for the next show in the James Bond series. It was more like hanging out at the scroll store in case there were any new prophets in the pipeline.

I bet nobody at the time thought to themselves, “Young David’s poetry is inspired by God.” It’s not the most lyrical stuff. There are exceptions. Everybody has heard of Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” But that one was only, let me check, six verses. Probably the shortest of all the Psalms. Take a hint, David: what did we do to deserve the 176 verses of this monstrosity of Psalm 119? A hundred and seventy-six verses. No wonder it came up when I opened to a random page: it fills half the Bible by itself. You can imagine the daring Hebrew editor who said, “Why don’t we cull out the worst of these psalms? Publish the best; maybe offer the rest in a supplementary volume for the king’s hardcore groupies.” Next thing you know, that editor has been drafted and finds himself in an army unit fighting the Midianites, or whoever was standing in for the Palestinians at that point.

When David wrote Psalm 119, he was probably just one more busker, like those guitarists playing in subway stations and on street corners. My bet was, his poetry made it into the big leagues only because he became king. History is written by the victors; maybe the Psalms had to be too. And David definitely was a victor: if memory served, there was a saying, somewhere in the Bible: “Saul has slain his thousands, and David his ten thousands.” So, wow, good for you, and for God, and for another one of those rules: “Thou shalt not kill.” Win-win, all the way around.

What we seemed to have, here, was a forerunner of the present-day sanctimony in which your televangelist gets up in front of the camera and rants about ungodliness, and then goes off and buggers boys or robs his congregation’s elderly members or whatever the scandal du jour may be. It’s like a version of Thoreau’s advice. Thoreau said, “If you see someone coming to help you, run for your life.” Here, the rule is, if you hear someone preaching, “Thou shalt not steal,” make sure you still have your wallet.

Which, as I thought about it, raised the question of whether David was in fact even the author of these psalms. What I recalled was that he sent Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah the general, into a battle where he would be killed. This is the mind of someone who, after shipping that editor off to the Midianite front, would look at the poems written by that banished editor, decide that they should not just go to waste, and claim them as his own. When the king says, “Have I ever shown you the fine poems I composed as a young singer in the subway?” you don’t reply, “David, do you think I don’t remember how we spent our days smoking Turkish hash?” You say, “Your highness, it is lovely poetry indeed.”

I mean, yes, no doubt David was a skilled general. But this is not Julius Caesar we’re talking about. This agent of God’s will did not quite manage to united the known world under his brilliant leadership. Not quite. His sprawling kingdom would have fit inside the borders of, what, New Jersey? Lord, thy works are a marvel to all who witness them, thy laws a testimony to thy wisdom, their observance the pride of thy chosen people.

Chapter 5

L’Chaim/Gesundheit

The weird sense of time continued. By this point, it felt like I had been writing for months. And yet I only had four chapters finished. Also, as far as I could recall, I had not slept.

I opened the Bible and put my finger on a verse. Here is what it said:

James 5:14. Is any sick among you? let him call for the elders of the church; and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord.

Now, I could not really fault those early Christians for making the best of a bad situation. You’re a persecuted minority. You’ll be thrown to the lions if the authorities even find you with a copy of – well, of whatever New Testament books had been written and distributed, at the time when James wrote. Or I guess the lions came later.

Point is, they were dealing with limited healthcare resources. Even if you could afford a doctor, the doctor would just pour lye on you, or make you drink urine or something. Hell, yes, have the elders pray over you – what do you have to lose? It’s safer than some of the alternatives. I wasn’t sure what the purpose of the oil would be, other than to make you slippery.

The instructions weren’t specific as to what the elders were supposed to pray for, or how long they were to go at it. Would it be OK to say, “Lord, I personally do not like this person, but please heal him anyway, just for the sake of appearances”? Or did they really need to put heart and soul into it, throwing themselves down on the floor and rending their garments and gnashing their teeth? Although I knew that the gnashing of teeth was a biblical concept, I had never been clear on whether it would involve grinding them together, or chomping down and then releasing, and what noises would accompany this act. But clearly it meant something serious.

The passage also had a distinct sex bias. Let the “elders” pray over “him.” What if the sick person is a girl – would she not get the prayer therapy? Since the elders would be greybeards, maybe a sick girl’s illness would require a convocation of the congregation’s battleaxes? Maybe they would not be allowed or expected to pray; maybe instead they’d just sit around and trade stories. Maybe women mystified James. God only knew what made them tick. He may have decided that this was a can of worms best left closed. He only had so much papyrus, and no doubt other things to say within the space allotted.

But I didn’t mean to be writing a Bible commentary, here. My mission was not to find fault with the Bible per se. My mission was to use it to provoke and structure a presentation of the things I wanted to tell people during my life. What mattered to me were not the historical realities surrounding people like James and King David. Those people mattered to me only because of their direct and indirect impacts on the world in which I had lived – direct, because there were people who had made that world a worse place through their faith in writers like James and David, and indirect, because they exemplified beliefs and tendencies that did so much harm.

The direct harm caused by this passage from James was that it became one more way in which Bible-believers fought against anything new and intelligent. Long after medicine had developed into a relatively scientific profession in which people were expected to test hypotheses and experiment with alternate solutions, our world was still cursed with these flat-earthers who considered it sinful to do anything other than pray and then watch their kids die. The idea was that God was smarter than the doctors. If the child dies, it was his will – implying that modern medicine was not his will.

I mean, no doubt God could play a pretty good hand of poker, but deliberately stacking the deck to put him on the losing side seemed a tad disrespectful. My God is so great and wonderful that I can portray him as a complete moron and he will still love me – and, praise God, he will send you to hell, where you belong for picking on saints like me.

The people who bought only part of this fiction would not be very happy either. They would believe the propaganda – the claim that God wrote the Bible, and thus was behind James’s instructions – and then they would be bitter about the implications. I prayed, but God let my baby die anyway; therefore, I hate God. It would never occur to many of these people that possibly none of this had anything to do with God – that he didn’t inspire James to write those words or that, if he did, he only meant to be conveying a message to the actual recipients of James’s letter.

Like, instead of the mysterious God who would fool around with having James write an ordinary letter to convey secret divine instructions to billions of people, why not a straight-up God who would be a kindhearted and practical communicator? That, over there, is just a letter from James; this here is my official announcement to the people of the world. I want to be clear about it, so there is no confusion.

That’s not God’s style, if you believe the believers: everything has to be tricky, because this is how you fool people and find your true friends. And what friends this tricky God had found. Along with the philandering preachers and the baby-killing morons, he had millions of believers who were ready to do anything to praise his name. Anything. Even making him out to be heartless and stupid, and incapable of composing a simple message without sowing dissension and ultimately murderous hatreds spanning centuries. We praise the God who requires our assistance to bail out his inept scriptures; we love the God who has left us to contrive excuses for the Bible’s patent absurdities. In a world providing no immediately obvious object of worship, the nature of the object invented tells you a lot about its worshiper.

Not that all of my world’s fundamentalists did still believe in faith-healing. People seemed to come around to reality at different rates. Some would stay holed up in their hermitage, back that long lane with the mean dog, long after others gave up and moved to town. Many believers had grown to appreciate the merits of a staged retreat, that is – caving in on modern medicine when that became convenient, just as their great-grandparents had accepted that dancing might not be sinful after all (if only because that’s how they had met their future spouses), but still holding the fort on the evils of television.

It turns out that God did not intend to be taken literally about faith-healing, except when it seems to work – but he definitely did mean to be taken literally (and don’t ask me how I know this) in all cases regarding the Ten Commandments, except for the ones involving people like King David. Or if that’s not worded quite right, let me know and I’ll check again with my theologians and scriptural lawyers.

This got to some of the direct harms wrought in my world by certain uses of that passage from James. I would have to get to the indirect harms later.

Chapter 6

The Sons of Lotan

This time, I drew one of those Bible passages that you look at and ask yourself, who in the world would care about this?

1 Chronicles 1:39. And the sons of Lotan; Hori, and Homam: and Timna was Lotan’s sister.

I went back to the start of 1 Chronicles chapter 1. It started with Adam, and kept listing names up to . . . I dunno. I started flipping pages, but at chapter 4, I realized I didn’t care, and anyway it would have nothing to do with my purpose here. The sons of Lotan were apparently some people who were born, lived, and died at some point in the history of the Hebrew nation.

This reminded me of the first chapter of the New Testament, in the book of Matthew. It traced the lineage of Jesus, starting from somewhere. From David, I suspected, because the word “lineage” recalled a Bible passage that I think I’d had to memorize for a Christmas play, when I was a little kid: “of the house and lineage of David.” Apparently it was important that Jesus was demonstrably a descendant of David. This was long, long before God invented DNA testing.

But to whom was it important? In the case of the New Testament, not sure. I had been told – did I mention that I had been a student of religion myself, for a while, back in my youth? – that of the four Gospels in the New Testament (i.e., Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), the book of Matthew was the Jewish gospel. It told the story of Jesus in terms that were supposed to be interesting to Jews. The idea was that the Jews would care about Jesus’s lineage, just as they apparently cared about whatever Chronicles was telling us. Or at least they used to care about this. I had never heard anyone, Jewish or Gentile, make much of these lists of names.

The idea seemed to be that God wrote this stuff for the ages. Some of it was for people like me, and some was for people who had died more than 2,000 years ago. Actually, a lot more of it seemed to be for them, and about them, than for and about me.

But that raised a question. I was already convinced that the God invented by the Hebrews and tweaked by the Christians was a hoax. They had no idea what they were talking about. And like many, I had been distracted by their hoax. Instead of focusing on the real God, or gods, or whatever there was, I had been busy with my theology study, and then with my reaction against it, and then with my reaction against those who did not react against it. All very nice, but not leading anywhere. Those people weren’t going to listen, think, or tell the truth. I was wasting my breath.

So, fine. I could make an effort to focus these pages – this book that, I guess, I was going to be writing – more on the real God, or at least on the issues that had been truly important in my life, and less on religious liars and frauds. No doubt about it: I did have other fish to fry.

Let us exercise that muscle, then. What could I learn about the real God, if there was one, from this passage in Chronicles?

It seemed I could learn that he . . . no, wait a minute. God was not my fricking grandfather. This was not some big old guy with a beard and a hellacious dick. I was not made in his image. This was an alien creature. If you believe the Christians, God knew everything and could do anything. Decidedly not human. And unless there was an undisclosed she-god, God was not male. Being a male without a female would not make sense. It would be like being the left-hand wire in the light socket. Incomplete circuit; nonworking device.

God, I felt, was probably an It – capitalized, here, for clarity of reference. God, the Thing. It needed only Itself to complete the circuit. God might dress Itself up as a man, perhaps to make Itself more understandable or familiar. But even that was unlikely: such a masquerade would generate mistaken ideas; it would be a deception to some and a discouragement to others. The man would not necessarily be very familiar to a woman, and even less familiar to a dog, the kind of dog that should go to Heaven and would probably be welcome there, as welcome as I was, if I was really not created in Its image – if this Thing found value in the endless varieties of things It had placed on the Earth.

So. From Chronicles, it seemed that I might learn something about God. God was not dumb enough to record Its thoughts in a book. Books become outdated as soon as you finish writing – except for this one. Seriously, any dumbass would anticipate that a list of dead Hebrews would have zero meaning to billions of people, a couple thousand years down the line.

I did used to think that at least God would have been smart enough to use video or holograms, if It had wanted to send a message that would avoid the difficulties of written texts, with their contradictions and their promotion of misunderstandings among readers. But that wouldn’t solve the Chronicles problem. This stuff about the sons of Lotan, or any other historical report, would have been as archaic in video as it was in print.

What I was seeing in Chronicles was what I had just seen in James. No honest person, uncorrupted by preexisting religious agenda, could construe the Bible as anything more than a human invention, not only in what people made of it but in its very concept. It was a device for the storage and perhaps the generation of human knowledge, the latter being the use I was trying to make of it. But where that fact might lead, I could not tell.

Chapter 7

Ye

Next time around, my finger came down upon the reported words of Jesus himself for the first time in this enterprise, in his Sermon on the Mount:

Matthew 5:14. Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on an hill cannot be hid.

And for all the times I had read or heard those words, I had never before encountered the thought that hit me this time. I got as far as the word “ye,” and I wondered: who is Jesus talking to?

It sounded like his disciples were the audience. But really, it was unlikely that crowd control in the first century would have prevented others from tagging along. He was probably talking to most but not necessarily all of his disciples, a few of their girlfriends or brothers or sisters, some groupies enjoying the Jesus groove but only able to do it part-time, a village idiot, a sharpie tagging along to see if s/he could get anything out of this crowd, etc.

My question: was Jesus talking only to these particular individuals, or to some among them (e.g., the designated disciples), or did “ye” include some larger section of the general public – like maybe the other groupies who couldn’t make it, or some random Joe in Tennessee in 1957 who would desparately wish not to be left out? Who was the “ye” who was/were the light of the world?

The analogy of the city on a hill suggests that he was not thinking in terms of multiple individuals, but rather of the group. You are the light, singular. You are a city on a hill. One city, not cities.

Maybe he meant, You, my disciples, will become the light of the world. But it didn’t sound like that. He didn’t seem to be laying out a projection of what as going to happen as the disciples become more sophisticated followers. He was talking in the present tense. Looking ahead to verse 16: “Let your light so shine before men.”

It certainly might have been a different kind of Christianity that I would have experienced, during my lifetime, if the message from our preachers had been that we were all in this together: that we were the body of Christ, that it was not a question of our individual experiences of courage or cowardice, on behalf of the gospel or otherwise; it was not even a question of our own personal salvation.

I mean, can you imagine what our world would be like, all these centuries later, if Jesus had been something other than a Jew? No offense to Karl Marx, but for the most part the Jews seemed to have always had an individualistic philosophy. They had not struck me as a particularly group-oriented people, except when defending their tribe against outsiders.

But Japan, or someplace like that: what if Jesus had landed in a collectivist society? Christians would have spent 2,000 years leading spiritual banzai charges, sacrificing their own interests left and right for the sake of their spiritual nation. It would have been obvious that Matthew was saying, You are all part of the city on the hill. You, all together, are the light of the world. The individual believer is nothing on his/her own; s/he can only aspire to become part of that larger conflagration.

What I had seen, in my life, was “divided we fall.” And no doubt about it, we had fallen. Everybody was in it for themselves; everybody could be bought off. The idea of being integrated into and subordinate to something larger than oneself was almost completely dead. With occasional exceptions – your platoon, perhaps, or your gang or team – the closest we got to that was in the parents who sacrificed themselves for their children. Even there, for every parent who truly put his/her children’s interests first, there was another who made a good show of it but who nonetheless remained first in his/her own priorities.

Or maybe I was understating. I knew there were teachers who would really struggle to help their kids, and doctors who really cared about their patients, and so forth. Lots of dedicated people in this world. Or, should I say, that world, the one I came from. I guess the point was more that the system tended to be set against these people. Doctors got burned out from the malpractice litigation. Teachers got hassled by the principals and the parents. It was dog eat dog. That was the real problem.

I didn’t know that it had always been like that, or that it had to be that way. I had occasionally seen Asian girls walking together, holding hands, and I had seen that kind of exceptional closeness in some European literature from previous centuries. Before the industrial era, I think. Even within my own life, there had been a sweetness in the rural community where I grew up – not perfect, not shared by everyone, but definitely there nonetheless – that had since vanished.

Somehow, we had wound up with an almost completely selfish life, and world, in which even the question of salvation was to be decided, in the end, by how well you could look after your own soul. Sure, you could preach to others; you could tell yourself that you really cared about what happened to them; but it was all too likely that what you really cared about was trying to avoid feeling guilty for abandoning them. It would be a rare Christian who would say to God, I’m not going with you unless you take my friends too – a Christian who would not only say it, but live it, refusing to have anything more to do with that God, living love for one’s friends instead of just talking about it.

I didn’t know what Jesus had in mind. But it did seem that what needed to happen in the world – what I had wanted to say to people, without necessarily having thought it through to this extent – was that we needed to get away from the extremely selfish, individualistic worldview that made selfishness and corruption the only sensible way to live. I wasn’t sure if this was the whole story, but it seemed that we had gone down a blind alley – one that might very well have been created or abetted by the Hebrew scriptures – in which it was all about those who succeeded (at the expense of others, if necessary) or failed (and drew the concomitant punishment).

It seemed that, for the past 2,000 years and more, we should have been less preoccupied with detecting and punishing individual human imperfections, and more concerned with collective improvements and positive outcomes. We somehow needed to rediscover, or to invent, a creed that would value the character traits that made our societies worth living in: goodness, courage, honesty, and all the rest. We needed a life redeemed by the marvelous quality of the people with whom we would live it.

I really wanted to tell people that. I hadn’t seen it quite that clearly while I was alive. Now I did. And I guess that was what being dead was all about: looking back and seeing it all more clearly, but too late.

Chapter 8

Sheep?

God wanted me to have no delusions that It was leading my Bible verse selection process. Or at least I assume that is why God blessed me with a random flip to this passage:

Numbers 31:36. And the half, the portion for those who had gone out to war, was in number three hundred and thirty-seven thousand five hundred sheep.

I looked at that and I knew, in my heart, that that was a lot of sheep. And now I understood why they called that book of the Bible “Numbers.”

Given such a useless passage, I decided to take this opportunity to reflect further on my sense that time was passing and yet I was not sleeping. Maybe the reference to sheep reminded me of counting sheep. Or maybe sheep made me think of . . . uh, never mind.

I knew that what I had written, so far, would have taken only a few hours, or at most a couple of days, to compose; and yet by this point it seemed that I had been in my cell for weeks if not months.

I still wasn’t sure how I knew, or why I felt, that time was passing. There was no mold growing on the walls, no stubble on my chin. I didn’t have a mirror, but it felt like my hair had not grown at all. Still, there was a definite impression that I’d been at this for a while.

Maybe some of that was fatigue. Not boredom. I was interested in what I was writing. But it felt like work too. I had a lot to say; I wanted to write words that would make sense; and yet I also had to struggle with the awareness that this was not going to amount to anything, that it could not possibly make a difference in the life I had left behind.

It didn’t leave me with a sense of futility. It wasn’t like I would write a sentence and then ask myself, “Now, what was the point of going to that trouble?” My writing was like a kind of therapy, as Max had no doubt anticipated. It’s just that I did seem to be carrying a weight, in this knowledge that my words were going to be just for me.

As I thought about it, I realized there was more to it than fatigue. It was like that feeling you get in a dream, where you are in a place that you have never been in your real life – and yet it feels very familiar, like you’ve been there before, or like you’ve been there for a long time. Maybe you get that feeling because you’ve been there in previous dreams. Like maybe I had been here in previous thoughts. There was this sense of time depth – a sense that, when I resumed my writing in my cell, it was something I had been doing for quite a while.

I’d heard of dark matter, which I think was stuff that physicists could not detect directly, but they knew it was out there somewhere because, I dunno, there was too much gravity or something. There was a force, anyway, that they could measure, and the known contents of the universe did not amount to enough to explain that force. That’s what it was like: I was experiencing dark time. I was getting the effects of being here for weeks or even months, the fatigue and the sense of time passing, without any direct awareness or experience of that time.

Well. There were a couple of possible explanations. Maybe my afterlife brain was foggy: maybe it was taking me a long, long time to put my thoughts together, and maybe this version of my brain was also not very good at self-inspection. So I could be slow, and not know that I was slow. I knew that brains could be damaged in weird ways, so that was possible. But there really didn’t seem to be anything wrong with my brain otherwise. So this, I felt, was not the best explanation.

Another possibility was that, when I would pause to reflect, I would get lost in my thoughts, and my head would go down some rabbit hole of contemplation or unconsciousness, and minutes or months would be ripping on by. But if that’s where the time slippage was happening, you’d think I’d be able to pinpoint it: no sense of time slippage in the first two paragraphs of this chapter but then – whoosh! – suddenly, in the third paragraph, it feels like a month has gone by.

I tried to pay very close attention to myself, to see if there was even a trace of a lurch in time. As far as I could tell, there just wasn’t. My consciousness of time seemed to be smooth. The delays felt organic. Like, this was just how time worked here. Somehow, it seemed that – without brain damage, without anything different in what I was doing or how I was doing it – it would take a week, or something, to produce a chapter that I could have written in an hour or two on Earth.

Chapter 9

The Big Fix

This time, I hit pay dirt. Forget Numbers of sheep – this time it was a prophet, with a stirring vision of the future:

Isaiah 25:8. He will swallow up death in victory; and the Lord GOD will wipe away tears from off all faces; and the rebuke of his people shall he take away from off all the earth: for the LORD hath spoken it.

I guess I died too soon. This writing project was interesting, but I believed I might have preferred to let my death be swallowed up in victory instead. Victory over whom, I was not sure, but that’s OK: win first, ask questions later.

This, I felt, was one of the passages that the Christians would later seize upon, in the story of Jesus rising from the dead. He would have “victory o’er the grave,” as they sang in, what song was it . . . right, the Christmas carol: “Rejoice, rejoice / Ema-a-an-u-el / Shall ransom captive I-i-is-ra-el.” Jesus would rise from the dead, Isaiah tells us, and then the Lord God will wipe the tears off all faces, after a brief 2,500-year commercial interruption that Isaiah had forgotten to mention. Or however long it might take, because we had been waiting all this time and it still hadn’t happened.

The rest of the passage didn’t interest me much. God is going to take away the rebuke of his people of the tribe of Israel. I suspected Isaiah was thinking in the short term – they were in captivity in Babylon, or otherwise having a hard time, and that would end, but no doubt there was a different Christian interpretation. Or a dozen different Christian interpretations. Whatever.

What did interest me was the promise of a coming Golden Age, when there would be no more tears. God was going to bring this about. That’s why Bible believers did not bother to try to create a better world: that was God’s responsibility.

There never seemed to be any specifics as to how God would shape this Golden Age of no more tears. Was he going to make the other driver less of a pig, so that I wouldn’t get nearly run off the road on my way to work? Was he going to remake the world out of rubber, so that when kids tumble in the playground and planes fall from the sky, they just bounce?

My own prescription was a little different. I felt that people needed to take responsibility for setting things straight in real time, right now. This would be difficult even in the best of conditions. It was impossible in a mega-world of huge corporations, huge government, huge forces all around. Whatever you might do in that world, it would make no difference. Pick up the trash in front of your house, and it’ll be back tomorrow. You can’t fight the tide.

To believe that you can change the world, you have to live in a human-sized world, where your efforts make a visible difference. Looking to a Lord God for the fix was exactly the wrong thing to do. You’d need a federal government that would devolve to the states, and then devolve again to the cities, and yet again to the communities, with the cop on the corner being someone who lives on that same street. You’d need to splinter the corporations and then splinter them again and again, until sales and service are what you do for your neighbors and friends.

Beyond 150 people, I think the research said, your network is too big to have personal meaning, and you disengage. I wondered if people who lived happy lives, in communities that felt like real homes, would see any sense in having a Lord God bigger than the whole planet, promising pie in the sky. I wondered if a super-God was the placid person’s version of the criminal’s armory – a response big enough to counterbalance anything that the controlling authorities could muster.

Little Israel, surrounded by big adversaries, had probably always needed to believe that it held the trump card. It believed that it had survived all these millenia, not because it was propped up by the contributory superstitions of billions of Christians and Muslims, but simply due to its God, or its faith in Him.

Chapter 10

The Bigger Fix

The next passage my finger landed on was of the same nature as the last one, but on an even grander level:

John 1:12. But as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God, even to them that believe on his name.

Is your old deodorant leaving you in a stunk? Switch to the New God, and he will make you even bigger than a mountain. You will be a Son of God!

Nice promise, if you can deliver. I was thinking of the sons of God who lived in states like Mississippi – high religiosity, low income, low educational level, high crime . . . I couldn’t remember all the indicators, but it seemed that being a son of God was not all it was cracked up to be. I mean, pardon my irreverence, but some would say it sucked.

This marketing problem – this hype, this overselling – pervaded the life I had lived, positive and negative. People said, and were allowed to say, the most ridiculous things – and were especially likely to be believed by those most desperate for hope, and most in need of the truth.

The problem, I felt, was the so-called free press. Nothing free about it. You’ve got to pay the bills somehow. Paper and ink and printing press repairs aren’t free. So you run ads. And over the years, the people who design the ads become very good at it. They find ways to learn all about you, and they use that knowledge to push your buttons. If the websites of CNN or Fox News were boyfriends or girlfriends, we’d call them manipulative psychos, and run away screaming. But there on our daily computer, no problem, tell me more.

Of course, the free press also gives you people like me, toiling away here to express my opinions, feeling compelled to vent even when there was no audience at all. Maybe Max had endorsed this because the writing process would enable people to kiss goodbye the last of the unfulfilled fantasies lingering from their years on Earth. Maybe it oriented them to the weird sense of time and other realities of this afterlife. Hard to say.

My own little writing project was not, in fact, a demonstration of the free press. Writing does not mean publishing. To publish this book-in-the-making, I needed, first of all, a life on Earth, and secondly a publisher, or something providing approximately the same services, including a marketing and publicity department. Again, you got to pay the bills, and hype is what does that.

What John was illustrating, in this passage, was that there was no such thing as a belief too preposterous to be entertained by millions upon millions of people. Being a son of God might be a silly claim in the abstract. But just build it into a web of stories and beliefs about Jesus and David and, what do you know, it does not seem silly at all. Not too much to ask; just the way God does things.

Maybe the most remarkable part of the whole scheme was that people would cling to it despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It wasn’t just the sons of God in Mississippi. It was virtually anything that Christians would say – or, I supposed, Muslims or followers of any religion, modern or primitive. You could show people that they were horrible, that everything about their religion was a lie, that their preachers’ predictions had failed every time, and they would have an answer for you. They would come out with a passage about how the Lord tests our faith, or something.

There was a Harvard philosopher named Willard Van Orman Quine. Or Ormand. Something like that. His opinion, as I recalled, was that people can maintain a web of beliefs by making adjustments. No matter how you cut and slice, they will piece it back together. I believe some other philosopher pointed out that this was not quite right, but I didn’t recall the details of that argument. For present purposes, it seemed like Quine had the basic picture.

So what we got, with the free press, was not just a newspaper. We got a package, including some news and some advertising. The news part hyped and distorted the day’s actual developments; the ad part hyped and distorted the product’s actual capabilities; and together they trained us, over the years, to accept action movie heroes who would survive a hail of bullets and being hit over the head with a baseball bat, with nary a scratch or concussion. If we could be sons of God, surely a 110-pound woman could fly through the air and deliver devastating kicks and chops to the physique of a massive male adversary, armed with a flamethrower and a submachine gun, whose only true sin was to be the bad guy.

Chapter 11

A Crank

As I continued in this writing project, a certain fear grew in me. I had ignored it to this point, but now my random Bible flipping took me back to the Psalms:

Psalms 30:2. O LORD my God, I cried unto thee, and thou hast healed me.

I think what set me off was thinking about Max and therapy. Let us review my situation. I was in solitary confinement in the afterlife. Yet I felt a need to vent my opinions about things in my life on Earth, which had now come to an end. For this purpose, I was writing pages to express my views, with absolutely no plan or concept of how anyone would ever see them.

Or maybe that wasn’t quite true. I had vaguely thought that maybe Max or someone else would read what I had written. Max surely wasn’t the only other person here, wherever we were.

But now there was the question of what they would think, whoever might read these pages. No writer, familiar with the many undesirable reactions that readers can have, would naively expect someone to read what I had written and say to me, in all sincerity, that I had expressed matters with a clarity and persuasiveness never before encountered. Especially not Max, who probably had a much better idea of what was going on than I did.

There was, in other words, the fear that I was in need of healing, as the Psalm put it, and Max – well, if not exactly acting on the impetus of the Lord God of Israel, was at least proceeding in similar spirit.

To put it plainly, my situation seemed somewhat reminiscent of an aging crank, living by himself in a dirty little apartment in a dingy neighborhood, full of angry views about everything, and ready to share them with anyone who would listen.

This, I knew, was not me. I knew in my heart that I was sweetness and light.

Oh, all right. I knew that I was capable of being sweetness and light, on a good day, when I felt like it. I actually was pretty pleasant to people, as long as they didn’t cross me. I seemed to be accumulating pages, here, in an inadvertent documentation of the ways in which people had been able to do that.

Was that the nature of Max’s therapy? Was he giving me enough rope to hang myself, letting me bluster on and on about all the ills, real and imagined, against which I would have liked to protect the world, or the U.S., or myself?

I reviewed what I had written. I cannot say how long this took. When I was finished with my rereading of the preceding pages, I came back to the same mental place: I felt that I had made worthy points in an intelligible manner. This was not the idle ranting of a mentally ill individual. I was doing something that seemed at least somewhat constructive, in a place where entertainment was scarce.

I won’t say that these conclusions entirely reassured me. But it did seem that this was about the best I could do under the circumstances.

Chapter 12

Sex

My next spin of the roulette wheel brought me something interesting:

Song of Solomon 3:7. Behold his bed, which is Solomon’s; threescore valiant men are about it, of the valiant of Israel.

I guess it took a valiant man to stand guard around Solomon’s bed. Read the rest of Song of Solomon, and you start to see why.

Or maybe not. I didn’t actually remember much of Song of Solomon, other than that it was the one with the passages about sex and breasts and so forth. It didn’t fit into what the Christians of my lifeworld believed Christ was all about, so it was ignored. Couldn’t be completely deleted, thanks to those pesky Hebrews and their preexisting canon of scripture, but it certainly could be shunned, and it was.

I couldn’t quite make out who was being talked about in this particular passage. God, in his all-knowingness, had somehow overlooked the possibility that the modernizing English-speaking world would be saddled for centuries with a King James translation that would alternately entertain, thrill, and baffle his followers.

The book was called Song of Solomon. I thought that meant that Solomon was writing it. I flipped back to the beginning. Chapter 1, verse 2: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth.” So either Solomon was gay, or this was some woman’s words. Seems like something I should have researched, during my years of Bible reading, but somehow I never did, or else I forgot the explanation.

I guessed that Solomon had 60 men around his bed for reasons of security. This would be enough of a royal guard to protect him against anything short of a full-on military assault. But why not around the palace, or wherever he lived? My guess: he was as afraid of inside schemers, a quiet knife while he slept, as of external foes. I wasn’t sure where he would enjoy his sexual carryings-on. Surely not on the bed, in the presence of the Mighty Sixty. Maybe in the walk-in closet.

Then again, maybe he did do it right there on the bed, in full view. Maybe it was a group effort. Maybe he conducted seminars. In my time, I had encountered reason to believe that sexual repression was much more typical in Great Bend than in Manhattan. It was the Christians, not the Jews, who had made sex dirty and hidden . . . well, that’s not true, the Jews came up with the Garden of Eden and the fig leaf, but still there was definitely a difference. The Hebrews had evidently not seen Song of Solomon as a bad book, else it would not have been in their book.

It seemed to me that western culture was now experiencing an extended reaction against those centuries of Christian repression. There was not, after all, anything intrinsically exotic about sex. Our primate cousins, the bonobos, made a life out of it, screwing for all sorts of reasons, any old time. Not sure why the chimpanzees preferred war over love. We seemed to have inherited some of each. But the bonobos could do it endlessly without making a big deal out of it. My sense was that we would too, eventually, as the worst extremes of Christian belief slid into the past and people became more free to enjoy and use sex as a powerful tool for social harmony.

It wasn’t that I was personally waiting for that day in the presumably distant future. For one thing, I wouldn’t be there; I was dead. Besides, I was somewhat repressed myself. I would have felt a bit awkward, screwing people at the office; moreover, I had not a gay bone in my body. So I was already at a considerable disadvantage vis-à-vis the bonobos, if (as I vaguely recalled) they would happily do anyone, anytime.

The point was, anyway, that maybe we still had a juvenile thrill about sex because our culture was in a juvenile phase of getting over its hyperparenting Christian phase. Another couple hundred years down the line, sex would probably be established as just part of a normal life. Maybe David assumed as much. Maybe he had made a point of putting bonobos in the Jerusalem zoo.

Chapter 13

Love

I had wondered when we would be getting to this. Love is such a big deal in the New Testament. But now the moment had arrived:

Romans 12:10. Be kindly affectioned one to another with brotherly love; in honour preferring one another.

Years earlier, I had sat through plenty of sermons about eros, philos (or was it philia?), and agape, the ancient Greek words for the three kinds of love mentioned in the original New Testament texts. I didn’t remember from my long-ago study of Greek, but this passage seemed to be talking about philia. Christians had treated that as second-best when compared to agape, divine love. But in our world, any port in a storm. Any lovin’ is good lovin’.

At the moment, I was not inclined to harp again on the hypocrisy of Christians who talked a mean talk about love, but were then to be seen out there engaging in the most vile acts. I’d read Gregory of Tours; I knew they’d always been like that, as far back as the Dark Ages. Love was supposed to be powerful; it was what Christianity was supposed to be all about; and yet it was just not there.

But, as I say, at this point I was not inclined to go on about that. Stick the knife in, give it a twist, but then move on and whistle a little tune; that’s me. What I wanted to talk about, rather, was a bit of my experience of Christian love.

Part of what had got me into the theology thing, back in my youth, was the experience of being in a prayer group in my high school. We all loved each other. I mean, sure, it was mixed up with horniness and attraction and the lovely fragrances that those Christian girls wore. But nobody to my knowledge was actually getting it on, and meanwhile there definitely was a lot of innocent sweetness and mutual support. It was a really nice experience.

My feeling was that, by the time we got to the 21st century, the Christians were as corrupt as everything else, except that no doubt there were still idealistic teenagers. Christians as a whole were so preoccupied with their lies about a perfect scripture, and their political hostilities about abortion and so forth, that they just didn’t have time for love. Behavior of that sort would evidently have to be modeled by someone else, someone committed to being Christlike, someone who cared more about the practice of love than about the legalistic preconditions and complications heaped up in fundamentalist rumor and lore.

This, I guessed, was no job for anyone flying solo. Life was too full of harsh realities. To build up love, you would need a community. Not a nation or an international church or online group of some kind. A real community, right where you live. People still needed real hugs; they needed someone who would drop what they were doing to come lend a hand or a hundred bucks in a pinch. And it had to be shared. If it comes down to just one or a few people bearing super burdens to create a sense of community, you’re in trouble: those few overachievers will quickly get used up and burned out. There’s a reason why nobody else is pitching in, and that’s what you need to figure out before your community will get off the ground.

I had often wished I could have experienced the fellowship of first-century Christianity. My sense of it was that they all wore plain white robes, all treated each other as equals, all ate and socialized with one another. I guess that, like any utopian movement, it was bound to fall apart eventually, due to internal quarrels and/or external attacks. The worse problem is that it was apparently too weak to bounce back and become the dominant model for Christian communities worldwide, except to some extent in monasteries and convents.

I wasn’t sure what to say about that. Maybe my own experience was instructive: maybe real fellowship could only be experienced by young people, before everyone pairs off into their own private sexual worlds. I didn’t really believe that – I knew, and had experienced at times, that there could be bonhomie among adults. Maybe the real solution was to begin with that youthful bonding, and never let it end: structure society and the community to protect and build upon it, so that young people of the future would always have a place where they truly belonged.

Chapter 14

Eternity

The next time, the Bible fell open to a place where I had already opened it. I was going to have to make sure to shuffle the deck more thoroughly from now on. But at least my blindfolded finger landed on a different verse:

Psalm 119:160. Thy word is true from the beginning: and every one of thy righteous judgments endureth for ever.

Psalm 119, my favorite. All about the law, and about God’s righteous judgments. I’d already had my say on that, however; now I was interested in the “for ever” part. As everyone knows, the Christian God puts you in heaven or hell when you die, and that’s where you stay until the end of time – although special arrangements could apparently be made for Catholics and their purgatory.

Until I got here, I had not thought too much about the concept of eternity. I knew heaven sounded super-boring, standing around on clouds and singing God’s praises endlessly. There was a serious lack of vision, not to mention prudent marketing, in that whole scenario. If I was really in a Christian afterlife, here in my cell, I don’t know that anyone would be too excited about what I was experiencing. Behave yourself and avoid sin and go to church and believe on the Lord Jesus Christ for your whole life long – for this? I guess this could have been Hell, but with nearly the same conclusion: was this really that horrible?

It was not clear to me why David thought that God’s laws needed to endure forever. That would imply that human habitation would continue forever, and this was not what the astronomers said. They said that stars burn out, and that someday this would happen to our Sun too.

I wondered: would God have the same laws for aliens (and would those laws also endure forever) – laws about not copulating with your sister, or whatever they were going on about, in Bible books like Leviticus and Deuteronomy? Maybe aliens had no sisters. Maybe they had no Leviticus. This suggested a possibility: I might not qualify for salvation on Earth, but I might have a shot on the third planet rotating around Arcturis Minor, or whatever.

David’s concept of forever was surely just “a long time.” God, speaking through David, was surely not trying to make a precise statement of what lay ahead. Deuteronomy contained no information on how the ancient Hebrews’ descendants should proceed when building colonies on Mars, where there would probably be no sheep and goats to sacrifice, nor any temple to sacrifice them in.

For that matter, what did “forever” mean? I’d heard that mathematicians and physicists considered time a dimension, the fourth dimension, right along with the familiar three spatial dimensions. To measure space, we had length, width, and height. But we had only one functional time dimension, and really, only one direction within that dimension: forward. Wasn’t that like having only one spatial dimension? Like length: if that’s all you had, you’d be pretty limited. How tall are you? Sorry, I have to lie down to find out.

I could have used a better understanding of time-related dimensions as I sat in my cell. It had felt like it was taking weeks and months to write pages that would have taken hours on Earth. I had wondered if there was something wrong with me – if I was spacing out or going unconscious for long periods of time, cumulating into a sense of time passage that I could not quite pin down. That was still a possibility. But now it seemed that maybe there was nothing wrong with me, other than being dead. I might just be operating in a different kind of time.

The idea seemed to be that you can’t directly measure space with a ruler: you need to take measurements going in three different directions at the same time. That technique would work OK with spatial dimensions, with the aid of a little multiplication. But it would be useless with time: unfortunately, there is no such thing as measuring multiple time dimensions at the same time.

I wondered if maybe this, what I was experiencing now, was the real time – if maybe what we thought of as “time,” during my life on Earth, was somehow a distortion or a poor reflection of the realities. Like if you had to represent a video just using photos: you could do it, with something like Picasso’s “Nude Descending a Staircase” (if I remembered the title right) – a series of cubist snapshot-like images representing, I believed, a rebellion against the limits of the canvas.

You could represent real time with your clock, but you’d get a poor result. Some moments would drag by, like when someone would de-pants you in public, and for a very long fraction of a second, you’d stand there and see all the heads start to turn toward you, all the mouths start to open in laughter, before you could register the need for action and could get your hands down there to pull them back up. And at other times, you could lose days, months – in some cases, most of a lifetime – just by being busy and not really having the inclination and the opportunity to pause and reflect on it; and even if you did have such inclination and opportunity, there would still be the fact that you’re just along for the ride, with nothing much that you can do to slow it down or change what it means.

Sleep, I thought, would be an excellent example of what might be the distortion of time during our lives on Earth. Sleep was weird. You could lay your head down for a few minutes or hours and feel refreshed, or you could spend the whole night in a half-dazed state, waking up nearly as tired as you were when you started. Or how about the occasional dream that seems like real life, or those people who supposedly had dreams that predicted the future? Not to mention déjà vu and being unconscious.

Measurements with a ruler, I decided, were ways of interacting with space. To get a grip on time dimensions, I would need ways of interacting with time. In my cell here in the afterlife, I didn’t seem to have any new tools or abilities for that purpose. I did have this sense that time was flying by, but there did not seem to be anything I could do with that.

But I tried. I thought it might help if I could come up with different ways of understanding time. Maybe that would give me a clue on what these other dimensions might be like.

After thinking about it for a while, I decided there was a difference between mechanical time, as shown on clocks, and experienced time, like what I was actually feeling. I would interact with mechanical time by observing the clock; I would interact with experienced time by living through certain moments.

So when David referred to “for ever,” that seemed to be more like theoretical time. No actual clock was going to measure eternity, and nobody was going to experience it. Even if we lived forever in the future, we hadn’t lived forever in the past, so we had already missed out on half of eternity. And even the part that we did experience would only be a part of the eternal future. The rest of theoretical eternity would stretch out in front of us forever. We could never experience it all.

Seen in that light, David’s “for ever” was like the mathematician’s talk about an infinitely long line: it would be neither measured nor experienced. It was just something that might be able to happen in theory.

Chapter 15

Dust

I sat there for quite a while, just thinking about time. Eventually I realized that my logical division of mechanical, experiential, and theoretical time was very nice, but in the end it didn’t explain anything.

The problem at hand was entirely experiential. I was having weird time experiences. It wasn’t a matter of theoretical or mechanical time. I wasn’t theorizing very much about eternity, or watching a clock’s hands spin around. It was more of a psychological or social matter.

In my life, experiencing time had been like driving down a road: some of it was up ahead, and some was in my rearview mirror. I wasn’t usually too focused on the question of whether the road went on forever, and I certainly didn’t plan to measure it; I just wanted to cover the part I was on. Sometimes it went fast, sometimes it went slow, but it always went forward.

But now I realized that I’d been thinking of time simplistically. On the clock, sure, it passed at a steady 50 MPH. But in real experience, there were slowdowns and speedups. Sometimes it was the freeway; sometimes it was the traffic jam; sometimes it involved left turns and running over stray animals.

I wondered whether the time I had experienced in my life was more like a piece of string that somebody had gotten all tangled up. I picked it up, and it became mine. It had some knots and kinks. I couldn’t straighten it out, so I just wound it up in a ball, knots and all, and put it down somewhere.

So now, what if I was an ant, walking along that string? I’d be on that ball, going around and around. A real ant couldn’t follow the string through every knot. So another example: a piece of wire, knotted and tangled and wrapped into a ball. You’re an electron, a bit of electricity going through that wire. To you, it’s a linear process, going from one end to the other. Knots are irrelevant. But to anyone with a bigger perspective, once again, you’re actually going around in circles around that ball. The knots and tangles don’t change the big picture. The big picture is that, at some point, someone disconnects the battery and puts your ball of wire on a shelf and closes the door, and there you sit in the dark, wondering what happened to your feelings of significance.