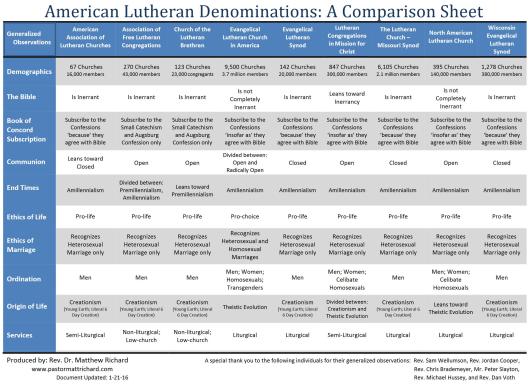

In traditional (also known, with some variation, as conservative, evangelical, fundamentalist, or Bible-believing) Christian practice in America today, the Bible is treated as if God handed it directly to mankind. People avoid asking the obvious questions – which language, which version, when, where? They just take it as, well, gospel.

Ministers trained in the traditional Christian denominations may learn that the truth is not so simple. For instance, in my first year of college, I was enrolled in the pre-ministry program at Concordia Lutheran Junior College in Ann Arbor, MI. If I hadn’t known it before then, presumably the full eight-year program for ministry would have notified me that the Bible did not simply drift down from heaven.

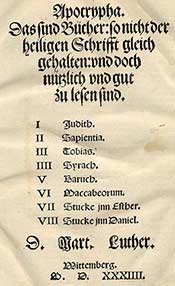

The Christian Bible consists of two or three sections. Christians commonly refer to the first section as the Old Testament. Starting with Luther’s Bible of 1534 A.D., some Bibles contain a middle section, called The Apocrypha, consisting of texts that some Christian denominations (e.g., the Catholic Church) accept as canonical – that is, as authoritative, authentic, holy, God-given – but that others reject or, at best, treat as useful for study (Wikipedia). The New Testament is the final section of the Christian Bible. In most Bibles in the U.S. today, there are only the Old and New Testaments, without the Apocrypha.

Contents

Summary

The Ketef Hinnom Inscriptions

Qumran

The Work of Scribes

The Old Testament Canon

Versions of the New Testament Canon

New Testament Apocrypha

A Speculative Psychohistory of Early Christianity

Selection Criteria for Books of the New Testament

Original New Testament Manuscripts

Translation of the Bible into English

Bible Interpretation

Dogma

Summary

The Hebrew Bible – what Christians call the Old Testament – originated centuries before Christ. Our oldest evidence comes from a small inscription onto silver. The Dead Sea scrolls, accumulated in the centuries surrounding Christ’s ministry, provide far more detail. Nonetheless, the oldest surviving manuscripts that contain more or less the full text of the Bible were created several hundred years after Christ.

From the early years, we have only fragments, and even the oldest of those were created a century or more after the biblical events they report. We don’t know how accurately the ancient scribes copied the originals, but we have a great deal of evidence that their work was imperfect. We have enough fragments to see that there were many variations among the ancient manuscripts comprising a given book of the Bible. In thousands of instances, scholars still don’t know – they probably never will know – exactly what the original author wrote.

There was, and to some extent there still is, disagreement over the “canon” that lists which books belong in the Bible. That issue remained unsettled for centuries after the last events reported in both the Old and New Testaments.

In the case of the New Testament, the Roman Catholic Church settled that question by force – destroying manuscripts that did not conform to its conclusions, and persecuting (sometimes executing) the people who wrote or distributed such manuscripts. The final selection of books of the New Testament was based largely upon acceptance of what the early church found most appealing, with the aid of some rather arbitrary decisions. If the church had been following the principles that various writers claim, our New Testament would look rather different.

Note, again, that this is merely a summary. The following sections present the details.

One section of this post presents my imagined re-creation of the flow of events in the first two centuries A.D. A key element in that speculation is the proposal that the first half of the second century saw considerable interest in consolidating the faith. An important point in that process: Marcion’s rejection of links between Old and New Testaments in the wake of the bar Kokhba revolt, when Christians had an incentive to distance themselves from the Roman persecution of Jews who participated in that revolt.

The Bible began to transition into the English language at or before the time of King Alfred the Great (c. 880 A.D.). That process picked up speed in the centuries leading up to the Reformation. The first authorized (i.e., non-persecuted) English translation arrived about 80 years before the famous King James Version (1611 A.D.). There are now more than 100 English translations.

Translation into English (indeed, into any language) is a complex undertaking. Demands for literal “word-for-word” translations generally do not make sense: in very many instances, across the 140,000 words of the Greek New Testament, the result of such an approach would be unintelligible. This post cites numerous examples where the translator must draw upon apparent meaning, and knowledge of the culture, to provide an approximation – in some instances, no more than an educated guess – as to what the original author meant.

Bible interpretation is a part of the final step of giving us today’s Bible. To varying degrees, people prefer translations that support their preconceived interpretations. Hence the translator’s decisions are driven by market pressures, in both economic and theological senses: if you don’t give people more or less what they want – including what their denomination authorizes – they won’t use your translation.

For purposes of giving us the Bible in a form that we will use, the effects of artificial intelligence remain to be seen. One may expect that AI will facilitate access to a great deal of commentary, from published (i.e., human) as well as artificially generated sources. Such commentary, along with automatically detected links among Bible passages and concepts, may usher in an age in which those who read or otherwise experience Bible texts are freed to follow biblical and historical threads across denominational lines, potentially merging the translation and interpretation functions. Conceivably AI could make immersion into the mind of the Bible vastly more interesting than traditional Bible reading tends to be.

Altogether, the process by which we came to possess the modern Bible has been fraught with gaps, imperfections, mysteries, falsehoods, guesswork, and politics. That could make it the work of a divine being. But there are no signs that it is the work of the God of the Bible. The manuscripts we possess, and the condition in which we possess them, are consistent with an entirely human effort, on the part of political powers based in Rome, to preserve materials conducive to one’s purposes, and to suppress materials contradicting one’s preferred narrative. It appears possible that interpretation, and ultimately the choice of Bible, would be greatly improved or at least helpfully informed by greater attention to competing early Christian manuscripts and beliefs.

With that summary behind us, we turn to the details.

The Ketef Hinnom Inscriptions

The first part of this post’s question is, how did we get the Old Testament?

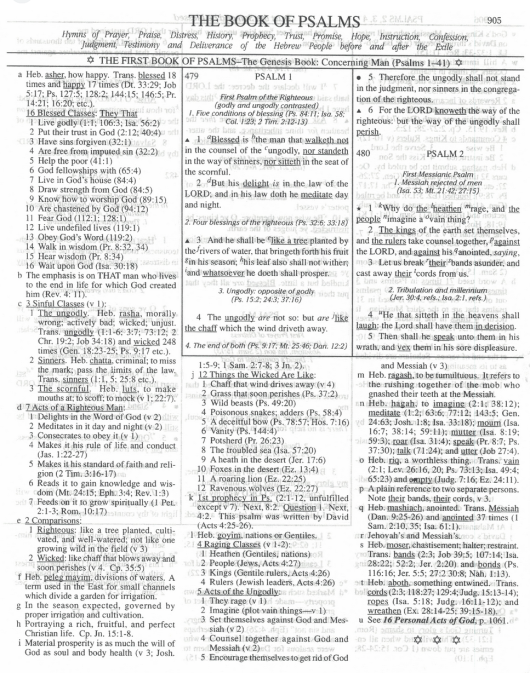

To that, there tend to be two sorts of answers. The traditional answer is that the books of the Old Testament were mostly written by the important historical Jewish figures who are literally or traditionally associated with them. For instance, David wrote the Psalms, and Daniel wrote the book of Daniel. Part of the modern (a/k/a liberal, nontraditional) answer is that, as Wikipedia says, “The oldest books began as songs and stories orally transmitted from generation to generation,” before eventually being written down on papyrus scrolls.

To illustrate the difference between those traditional and modern answers, we might consider the book of Numbers, also known as the fourth of the five books of Moses (i.e., Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy), collectively forming what is known in Hebrew as the Torah, and in Greek as the Pentateuch.

Reflecting the traditional view, Bible Gateway offers an Encyclopedia of the Bible whose relevant entry claims that the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt occurred sometime between 1440 and 1260 B.C., and that Moses (leader of the exodus) probably wrote most if not all of Numbers. By contrast, Wikipedia says, “The majority of modern biblical scholars believe that the Torah … reached its present form in the post-Exilic period (i.e., after c. 520 BC).”

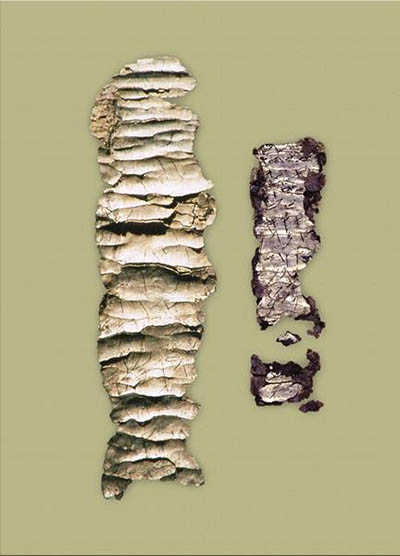

The Ketef Hinnom scrolls, unrolled

I chose Numbers as an example because, at present, it is the book for which we have the oldest physical evidence. That evidence comes in the form of two little silver scrolls, found at Ketef Hinnom, near Jerusalem, dating back to sometime around 600 B.C. On one of those scrolls, someone inscribed words similar to the text of Numbers 6:24-26 in today’s Bible (Biblical Archaeology Society, 2023; Barkay et al., 2004; Wikipedia). That choice is famous: “The Lord bless you and keep you: The Lord make his face to shine upon you, and be gracious to you: The Lord lift up his countenance upon you, and give you peace.”

Obviously, a blessing of that nature could be widely quoted; it could float around in the culture, independent of any book of Numbers. Indeed, that is exactly what it did, within the culture of my youth: it was the minister’s common benediction at our Lutheran church throughout my childhood, when I had no idea where it came from. Its existence c. 600 B.C. does not demonstrate that Numbers existed in final form at that point; the artisan may have been inscribing a widely approved sentiment that would not be combined with other materials to form Numbers until some later date.

Qumran

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran, starting in 1946, provided what are now some of our oldest copies of books of the Old Testament. Those manuscripts appear to have been created across a period of several centuries, c. 250 B.C. to 100 A.D. (Wikipedia).

By the time of discovery, the passage of millenia had reduced most of the original scrolls to fragments, mostly containing only brief bits of text. Fewer than a dozen scrolls survived as nearly complete texts of books of the Bible. (See Gnostic Society Library, n.d.; Martinez & Tigchelaar, 1999, p. 1311; Israel Museum, Jerusalem, n.d.; Florentino et al., 1992, p. 474.)

Even in fragmentary form, the scrolls show that, during those centuries, there was “no uniform text” comprising a settled version of the Hebrew Bible (Wikipedia; see also Tablet, 2013). To illustrate, Wikipedia compares three versions of Deuteronomy 32:43:

- One is a fragment found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

- Another comes from the Septuagint, a Hebrew-to-Greek translation created by Jewish scholars over an extended timespan, possibly starting as early as 285 B.C. and ending as late as 100 B.C. Wikipedia says “the oldest-surviving nearly-complete manuscripts of the Old Testament in any language” are two versions of the Septuagint created after 300 A.D. (See Sundberg, 1958, p. 213.)

- The third comes from the Masoretic text, prepared by Jewish scholars between 600 and 1000 A.D. The Masoretic text – the authoritative text of today’s Hebrew Bible – is memorialized in the oldest complete Hebrew manuscript of the Old Testament, known as the Leningrad Codex (1008 A.D.) (Wikipedia). (Law (2013) reportedly argues that, at least in some places, Luther would have been drawing upon a more ancient source if he had based his Old Testament upon the Septuagint instead of the Masoretic text.)

- One might expand that comparison by adding the Samaritan Pentateuch, composed in the early centuries B.C., which differs from the Masoretic text in more than 6,000 places.

(Note: a codex is the historical descendant of the scroll, and the ancestor of the book: it contains pages, like a book, but the pages are made of ancient materials (e.g., parchment) rather than paper, and are bound in a more primitive manner. For a look at a very old book, see my video from the Lilly Library.)

Briefly, Wikipedia’s comparison of that passage in Deuteronomy shows the Masoretic text missing things that appear in the Qumran version (e.g., a claim that God “will recompense the ones hating him”), and the Qumran version missing things found in the Septuagint (e.g., “And let all the angels of God be strong in him”). The point, for present purposes, is that the identities of the five books of the Pentateuch may have been established much earlier, but the exact contents of those books were still unsettled during the centuries when people used or lived in or around the caves at Qumran.

The Work of Scribes

In what one could interpret as a warning to present-day Christians who obsess on the text of the Bible at the expense of its principles, Jesus railed against the scribes of his day. Britannica (n.d.) explains that, in Jewish culture of that time, scribes were essentially lawyers, found at work in every village, typically drafting legal documents.

Within the scribal profession, some worked at the task of copying old Hebrew scriptures onto new parchment or other materials, so as to preserve them for future generations. That may sound straightforward. In practice, however, it seems that scribes could and often did produce works whose texts were not exact copies of the old documents they were copying from.

If we continue with the previous section’s attention to the ancient book of Numbers (above), we find Pike (1996, p. 174) indicating that the copies of Numbers found at Qumran varied considerably from one another. Barr (1987, p. 1) further indicates that Qumran provided “a Hebrew text which shows in some places a substantial variation from the text previously known to us” – from, that is, the oldest manuscripts we had prior to the discoveries at Qumran.

Taking one example, Jastram (1998, p. 265) studied what he called an “expansionistic” partial text of Numbers found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. In using that term, he was drawing upon prior scholars who had identified four stages in the treatment of ancient manuscripts by scripture-copying scribes:

In the first stage [i.e., before the book in question had an established status] there was still freedom to make major additions and alterations. In the second stage there was freedom for minor expansions and alterations [harmonizations or explanations]. In the third stage only what were perceived as mistakes in the [received text] could be corrected. And finally in the fourth stage not even obvious mistakes could be corrected.

In other words, scribes typically started out with a manuscript that had not yet been reified into a holy work that one dare not change. They felt relatively free to fix or improve it as they saw fit. But as the centuries passed, the most revered manuscripts were increasingly put on a pedestal, until the scribe was expected to achieve perfect copying without the slightest change. (Even then, various sources discuss examples of, and reasons for, scribal errors in copying.) Within those four stages of increasingly strict transmission, Jastram (1998) found that his selected Numbers manuscript, at Qumran, was still early in the sequence: scribes displayed a willingness to make relatively large changes to it.

To recap, the traditional view holds that Moses was the primary author of the so-called Books of Moses before 1200 B.C. In this view, the quality of the book of Numbers deteriorated, as scribes made mistakes in transmission. The liberal view is rather the opposite: Moses did not write the book of Numbers. Instead, it originally existed as an assortment of ancient stories and records, written and oral, that gradually coalesced over a period of centuries until finally, sometime after 520 B.C., they reached a form that was roughly similar to today’s version. Either way, from that point forward – as we know from the Septuagint, the Samaritan Pentateuch, and the Dead Sea Scrolls – the precise contents of the books of the Hebrew Bible remained subject to substantial variation until at least 100 A.D.

The Old Testament Canon

As just described, the wording of texts within the Hebrew Bible varied, from one source to another. But whatever their exact wording, when did authorities finalize the canon – that is, the list of books contained in that Bible?

According to Britannica (n.d.; see Lizorkin-Eyzenberg, 2014), Jewish scholars decided, at the Council of Jamnia (90 A.D.), that the books later identified as Apocrypha in Luther’s Bible did not belong in the Hebrew canon. Note that these were the close contenders for inclusion; there were many other Old Testament apocryphal works that did not attract comparable interest and support. Contra Britannica, the current view is that, in fact, there probably was no Council of Jamnia (Wikipedia; Lewis, 1999).

Catholic Answers (Rose, 2014) speculates that

[Jews] were still awaiting the advent of the New Elijah [whom Christians take to be] (John the Baptist) and the New Moses (Jesus). … Jews would expect these two great prophets to write books as well. Closing the Hebrew canon before the prophets’ advent, then, would have been unthinkable.

If that is so, it is not clear why the Jews did close the canon, apparently by 200 A.D. (New World Encylopedia, n.d.). What seems more likely is Neusner’s (1987, pp. 128-145; 1988, pp. 1-22) suggestion (see Wikipedia) that Jewish scholars circa 1 A.D. were simply not very interested in the concept of a canon. As discussed below, their eventual decision to do so may have been due primarily to a conservative desire to consolidate existing knowledge and/or to protect the Hebrew scriptures against possible corruption by popular revisionists, exemplified by Marcion in the case of the New Testament.

Sources cited in the previous section gave me the impression that the contents of many books of the Hebrew Bible gradually became more finalized, less open to change. The theory, there, was that this process unfolded as each individual book became more established. But I wondered whether the better explanation might be that, for Jews and Christians alike, the concept of scripture itself was changing.

For instance, maybe the Christians introduced the previously alien idea that, in effect, it was time for God to stop talking, because they had everything they needed from him, now that Jesus had come and gone: the gospels and the book of Revelation had pretty much laid out the divine plan.

The Jews may have become similarly receptive to the closing of their canon, though for a different reason. Maybe, with the fall of Jerusalem and the transition to Rabbinic Judaism starting in 70 A.D., or in the wake of bar Kokhba’s revolt (below), Jewish leaders concluded that the age of the kings and prophets was over, and it was time to firm up the scripture that would bind them together during what could be another Babylonian exile – during, that is, a potentially long period of dispersion. Britannica (n.d.) says that, ultimately, it is not clear exactly when or how – or, apparently, why – the Hebrew canon was settled.

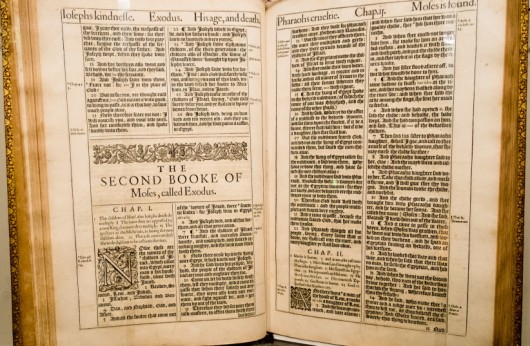

The finalization of the Christian Old Testament was more complicated. The Hebrew-to-Greek translation effort produced the Septuagint (c. 200 B.C.), with a structure that departed from the Hebrew Bible – dividing the Hebrew books of Samuel and Kings, for instance, and including books not found in the Hebrew scripture. As noted above, in 1534, Luther’s Bible would set the latter aside in their own section, labeled as “Apocrypha: These Books Are Not Held Equal to the Scriptures, but Are Useful and Good to Read.” In this, Luther seems to have followed the view expressed by Jerome (below) more than a thousand years earlier (Root, 2016, p. 9). New Advent (n.d.) contends, however, that Jerome’s view was both eccentric and incorrect, and explains that Catholics believe the so-called Apocrypha are more accurately characterized with the term “deuterocanonical” (coined in 1566 A.D.) meaning “second canon.”

Title page from Luther’s Apocrypha

Luther’s view, adopted by almost all Protestant denominations, was consistent with his prioritization of Jewish scholarship over that of the Catholic church. In favoring the Hebrew canon, Luther seems to have followed the earliest known Christian canons, which acknowledged few if any of the apocryphal works. For instance, the first Christian list of canonical Old Testament books (and the term “Old Testament” itself) seem to have been produced by Melito (c. 170 A.D.): his list excluded the Apocrypha – but possibly also the book of Esther.

While that move on Luther’s part may seem to make sense, it may have departed from prevailing practice in the first-century church. Catholic sources contend that the apostles and other writers of the books of the New Testament drew frequently on texts and ideas found in the Septuagint (e.g., Scripture Catholic, n.d.; Akin, n.d.; contra Salter, 2021). New World Encyclopedia (1 2) argues that the early church did substantially approve the deuterocanonical books of the Septuagint. Schenker (Foreword to Daley, 2019, p. XIV) agrees that, in the first several centuries, “the churches of the Greek, Syrian, and Latin speaking areas … accepted the view that their [Old Testament] was not completely identical in all points with the Jewish Bible.”

The Catholic church finalized its canon (including most of the deuterocanonical books) in 382 A.D., at the Council of Rome. The man whom Catholics now call St. Jerome promptly commenced a project that, in 405 A.D., produced the Latin Bible that eventually became known as the Vulgate. The Vulgate supposedly included a new Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible, but apparently relied to some extent on older Latin translations of the Greek Septuagint’s apocryphal books (Wikipedia; Britannica, n.d.). The Catholic church adopted the Vulgate – though centuries would pass before it fully replaced the older Latin version in practical usage – and has retained it (with revisions) to the present day.

Originally, the Hebrew Bible seems to have had 22 books. Josephus (c. 95/1926, p. 179) quoted that number, but did not name the specific books, and may have been reflecting just one view, within canonical debate at that time (Wikipedia; Bruce, 1988, p. 58). The first ancient source saying there were 24 books in the Hebrew Bible (i.e., the number found in today’s version) was the apocryphal book of 2 Esdras (c. 95 A.D.) (see Orthodox Essene Judaism, 2016).

Wikipedia’s table and other sources tell us that the original 22 books of the Hebrew Bible became (with splitting of books and the addition of the Apocrypha) the 51 books of the Septuagint, later evolving into the 46-book Old Testament of the Catholic Bible, the rather different 46-book Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo canon, the 49 books of the Eastern Orthodox canon, the 39-book Old Testament and 14-book Apocrypha of Luther’s Bible, and the simpler 39-book Old Testament of modern Protestant translations. Wikipedia suggests that the larger numbers of books in non-western (e.g., Eastern Orthodox, Syriac, Armenian, Coptic) Old Testaments were due to a greater willingness to recognize spiritual value in books that the Catholic and, more so, the later Protestant churches excluded.

Versions of the New Testament Canon

As just noted, early Christian sources seem to have produced canons – notably the Bryennios List, whose antiquity is disputed, and Melito’s canon (c. 170 A.D.) – that listed books from the Old Testament era. The first effort to formalize Christian writings as official additions or alternatives to those Old Testament canons occurred around 140 A.D., when Marcion suggested there were two Gods: the vengeful creator described in what we now call the Old Testament, and the Heavenly Father described in writings about Jesus. Multiple scholars suggest that, while Marcion was deemed a heretic for his trouble, at least his canon provoked the early church to move toward its own statement of a New Testament canon.

Being included in the canon would be a challenge for books that did not yet exist. While it is difficult if not impossible to identify the precise date when a given New Testament book was written, certain factors can help at least to narrow down the timeframe of composition. Those factors can include internal contents (e.g., reference to a contemporary political event), external references (e.g., where some ancient Church father refers to the document), archeological context (e.g., finding a partly burned scroll in the dateable remnants of a building that burned down), use of terminology that did not exist before a certain date, the date or era of an identifiable handwriting or literary style (if not faked by a later pretender), and radiocarbon dating (but note that parchment and papyrus could be scrubbed and reused, so the text might be newer than the material) (see Text & Canon Institute, 2022; Wikipedia 1 2 3; Ehrman, 2015).

Except where one believes that a book’s author was foretelling the future (as in the belief that Revelation was written before 70 A.D.), common sense pegs the earliest possible date at the time of the reported events. For instance, a book providing details about the life of Jesus was probably not written before Jesus existed. The latest possible date is the date of a physical manuscript. If we have a written copy that can be reliably dated at, say, 150 A.D., we infer that the original version of that document must have been written by then.

Such factors can still leave a lot of latitude. Bernier (2022, p. 3) offers a table contrasting scholars’ proposed earliest, middle, and latest possible dates when the books of the New Testament were written, and argues that the early dates are most likely. Conservative Christians (e.g., Bible Gateway, n.d.) tend to favor early dates, so as to encourage trust in the accuracy of New Testament. An early date minimizes the number of years during which stories related to Jesus may have been floating around in oral or informal (e.g., poorly or incompletely) written form, subject to inaccurate recollection and to distortion, before becoming relatively finalized in texts similar to the ones we possess today.

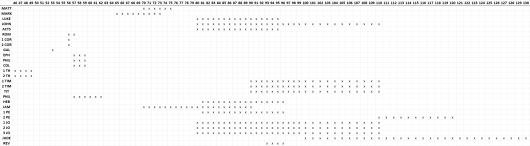

According to Bernier’s list, scholars favoring early dates tend to believe that the books of the New Testament were all composed between 45 and 68 A.D. By comparison, in Bernier’s list of the view of scholars favoring late dates, only seven were written before 70 A.D.; most were written between 100 and 150 A.D. A chart of Bernier’s list of middle dates – which he says are favored by a majority of contemporary New Testament scholars (see Wikipedia) – displays early dates (46-62 A.D.) for ten of the New Testament’s 27 books, middling dates (80-110 A.D.) for 12, and dates elsewhere in the 65-130 A.D. spectrum for the rest (right-click to open in a separate tab, Ctrl-Plus to enlarge):

Years of composition of New Testament books – distribution of moderate estimates

Within such general timeframes, we may consider several elements of particular interest. First, returning to Marcion (c. 140 A.D.), we might expect that his attempt to form a canon would make specific note of the books he had encountered. Wikipedia says, “Marcion’s writings are lost …. Even so, many scholars claim it is possible to reconstruct” many of his views, by reading what critics said about them. This appears to be the basis on which Schaff (1819-1893/1910, p. 301) inferred that Marcion specifically rejected everything in the Protestant New Testament except an altered version of Luke, Romans through Thessalonians, and Philemon. But it is not entirely clear which books Marcion did reject. Ehrman (2003, p. 107) observes that perhaps some “were not as widely circulated by Marcion’s time and that he himself did not know of them.”

Another early canon, the Muratorian fragment (full text), is an 85-line text, apparently copied in an Italian monastery in the 8th century, originating in a document that seems to have been created sometime between 170 and 400 A.D. If it was first composed around 170, it would be (as claimed by New Advent, 2021) “the oldest known canon … of the New Testament.” Unfortunately, that seems not to be the case. Rothschild (2018, pp. 79-82) concludes that it is a fourth-century fake that tries to position itself as a second-century text.

The fourth century would be of interest because that seems to have been when the church finally got serious about forming a New Testament canon. According to Ehrman (2003, p. 3),

The first instance we have of any Christian author urging that our current twenty-seven books, and only these twenty-seven, should be accepted as Scripture occurred in the year 367 CE, in a letter written by the powerful bishop of Alexandria (Egypt), Athanasius.

Progress before then appears to have been slow. New World Encyclopedia (NWE, n.d.) tells us that Irenaeus argued, in 170 A.D., that the four gospels were “pillars” of the church, possibly in response to Marcion’s decision to keep only an altered version of Luke. Elsewhere, NWE (n.d.) admits “a good measure of debate in the Early Church” regarding the canon, with particular reference to disagreements, starting in or before the early 200s A.D., about the canonicity of a half-dozen books located toward the end of today’s New Testament, sometimes collectively referred to as the antilegomena (below).

NWE (n.d.) disputes the foregoing quote from Ehrman: NWE contends that Bishop Cyril of Jerusalem “formally established” the “canonical Christian Bible” in 350 A.D. That is incorrect. Cyril included Edras and Baruch in the Old Testament and excluded Revelation from the New (Lane, n.d.; New Advent, n.d., ¶¶ 35-36). Revelation (and those and other Old Testament apocryphal works) were similarly treated at the Council of Laodicea (363 A.D.), contradicting NWE’s (n.d.) further claim that that council “confirmed” the Christian canon.

The Roman emperor Constantine I called the Council of Nicaea (325 A.D.) to respond to the Arian heresy, which held that Jesus was distinct from and subordinate to God the Father. That Council remains famous as the birthplace of the Nicene Creed. The Council did not, however, reach any conclusions regarding the canon. The notion that it did so originates in an old fake history which claimed that the Council chose the books of the Bible by placing them on an altar and keeping the ones that did not fall off.

In short (as most sources seem to agree), in the words of Britannica (n.d.), Athanasius “delimited the canon” in 367 A.D. But Britannica’s own remarks somewhat undercut its suggestion that Athanasius thus “settled the strife.” Among other things, the Greek churches continued to doubt Revelation; the Codex Alexandrinus (dated c. 400-440 A.D.) included New Testament apocryphal works not appearing on Athanasius’s list; and the Syriac canon did not even include Paul’s letters until the third century, and would continue to differ from the Roman canon for another 400 years.

Christian History Institute (Thiede, 1990) observes that the Roman church wrote Codex Vaticanus – “the oldest extant copy of the Bible” (Wikipedia) – in 340 A.D., suggesting a careful prior effort to investigate and display the full text of the books that were going to be included in the Athanasian canon. Even so, Thiede says, after 367 A.D. there were many subsequent instances in which scholars disputed that canon, such as the decisions by Didymus the Blind to treat several books of the New Testament apocrypha (below) as canonical (see Ehrman, 1983, pp. 11-19).

The point seems to be, not that Athanasius laid down an iron rule from which nobody dissented, but merely that no such dissents were effective in changing the New Testament canon that he established in 367 A.D. As Thiede (1990) puts it,

Martin Luther would dearly have loved to have excluded James, which he regarded as contradicting Paul. Indeed, why not add Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” of 1964, as was suggested by some modern writers, or eliminate epistles [that exist in today’s New Testament, but are] currently thought to be inauthentic?

The “closed canon” that prevails in all Christian churches forms a consensus that prevents such eccentricities. And that canon can be traced back to Athanasius, and to the year 367, which justly remains an important date in church history.

Wikipedia states that church councils in 397 and 419 essentially ratified the Athanasian canon – but also, oddly, that “full dogmatic articulations of the canon” by Rome and other churches would only begin more than 1,100 years later, starting with the Canon of Trent (1546 A.D.) – two months after Luther died.

New Testament Apocrypha

The preceding section introduces the fact that there were apocryphal works, not only for the Old Testament, but also for the New. Old Testament apocrypha typically pertained to ancient Jewish themes linked to the Hebrew Bible, and were often written in Hebrew (Davies, 1939), while New Testament apocrypha tended to address Christian themes (e.g., stories about Jesus, teachings of the apostles) (Wikipedia). Together, these form the biblical apocrypha, mostly written between 200 B.C. and 400 A.D.

(Note: some sources refer to pseudepigrapha. That word simply means “false attribution.” Example: Pseudo-Aristotle includes the spectrum of authors whose works were falsely claimed (by themselves or others) to have been written by Aristotle. Within biblical literature, modern scholars consider the book of Daniel an example of pseudepigrapha because, contrary to its own claim, it seems to have been written 400 years after the real Daniel. Many scholars hold that numerous canonical New Testament works are pseudepigraphical. For instance, Britannica (n.d.) states that the Letter to the Hebrews, attributed to Paul, was actually written after his death. A non-canonical New Testament example is the so-called Gospel of Barnabas, written in the late Middle Ages but purporting to have been written by Barnabas, a disciple of Jesus. One obvious motive behind pseudepigraphy would be to seek greater status or attention for a work. Another motive in some cases is the desire to honor or give credit to a leader or teacher who is believed to have made the work possible, or to position the work as part of that person’s rightful legacy. (See Garrison, 2012.) In any event, this post does not dwell upon the phenomenon of pseudepigraphy.)

There is a long list of New Testament apocryphal works, mostly hailing from the early centuries A.D. It includes, among others, a variety of gospels (e.g., Life of John the Baptist; Gospel of Peter), Gnostic dialogues with Jesus (e.g., Gospel of Mary), Sethian texts (e.g., Trimorphic Protennoia), Acts (e.g., Acts of Paul), Epistles (e.g., Epistles of Clement), Apocalypses (e.g., Apocalypse of Stephen), and so forth. There are also numerous fragmentary works (e.g., The Fayyum Fragment) and lost works known only from third-party references (e.g., Gospel of the Seventy). New Advent (n.d.) summarizes some New Testament apocryphal works. Ehrman (2003) provides much more detail on some.

There would probably be many more apocryphal works, and more information on developments in the first centuries of the church – but Britannica (n.d.) states that, to those whose Christian beliefs were in the process of becoming dominant within the church, such books conveyed the kinds of seemingly “obsolete” beliefs that “church leaders were trying to prune and shape from the 1st century onward” and, elsewhere, that “virtually all [New Testament apocryphal works] advocating beliefs that later became heretical were destined to denunciation and destruction.” (For fictionalized development of related themes, see Brown’s (2003) best-selling Da Vinci Code.)

Britannica (n.d.) cites Marcionism (above) as an example of beliefs that the church sought to suppress: “A number of popes … were involved in fighting the spread of the Marcionite movement.” Britannica (n.d.) likewise describes Montanism as “an attack on orthodox Christianity” whose “writings have perished” because “mainstream Christianity vigorously opposed” it (Tabbernee, 2007, p. 404). As another example, Jewish Christians reportedly continued to worship in synagogues for centuries, apparently encouraging “[v]arious forms of Jewish Christianity” to survive until sometime in the 400s A.D. and to canonicalize “very different sets of books, including Jewish-Christian gospels” that were gradually eradicated from the historical record.

The forms of belief now called Gnosticism were prominent among those suppressed views and texts. While that line of belief deserves a closer look, I will simply summarize it by quoting Wikipedia at length:

Gnosticism [Greek for “possessing knowledge”] … is a collection of religious ideas and systems that …. [distinguishes] a supreme, hidden God and a malevolent lesser divinity (sometimes associated with the God of the Hebrew Bible) who is responsible for creating the material universe. … Gnostics considered material existence flawed or evil, and held the principal element of salvation to be direct knowledge of the hidden divinity ….

Efforts to destroy [Gnostic] texts proved largely successful, resulting in the survival of very little writing by Gnostic theologians. … For centuries, most scholarly knowledge about Gnosticism was limited to the anti-heretical writings of early Christian figures …. There was a renewed interest in Gnosticism after the 1945 discovery of Egypt’s Nag Hammadi library, a collection of rare early Christian and Gnostic texts ….

Gnostic belief was widespread within Christianity until the proto-orthodox Christian communities expelled the group in the second and third centuries …. [It originated] in the late first century AD in nonrabbinical Jewish sects and early Christian sects [but had roots in Zoroastrianism, among others]. …

[In] the angel Christology of some early Christians … [such as in The Shepherd of Hermas,] Jesus is …. [perceived as] as a virtuous man filled with a Holy “pre-existent spirit”. … [Some Gnostics saw him] as an embodiment of the supreme being who became incarnate [or, in other views, had no physical body,] to bring gnōsis to the earth, while others … [considered him] merely a human who attained enlightenment through gnosis and taught his disciples to do the same. …

Initially, [Gnostics and proto-orthodox Christians] were hard to distinguish from each other. … [Bauer (1979) observed that what would later be called] “heresies” may well have been the original form of Christianity in many regions …. [Pagels (1979, 1988) reportedly contended] that “the proto-orthodox church found itself in debates with gnostic Christians that helped them to stabilize their own beliefs.” …

[Gnostic texts] may contain information about the historical Jesus …. [They also seem to convey an earlier view that the kingdom of heaven is already here, and not a future event. But possibly that view was a 2nd-century revision, adopted when the end time failed to arrive.]

The prologue of the Gospel of John …. [arguably] shows “the development of certain gnostic ideas, especially Christ as heavenly revealer, the emphasis on light versus darkness, and anti-Jewish animus” … [Some see John as] a “transitional system from early Christianity to gnostic beliefs in a God who transcends our world.” …

Tertullian calls Paul “the apostle of the heretics” because Paul’s writings were attractive to gnostics, and interpreted in a gnostic way, while Jewish Christians found him to stray from the Jewish roots of Christianity. … Many Nag Hammadi texts … consider Paul to be “the great apostle” … [partly because] he claimed to have received his gospel directly by revelation from God …. However, his revelation was different from the gnostic revelations. …

[Elsewhere, Marcion’s] teachings clearly resemble some Gnostic teachings. … [and] snake handling played a role in ceremonies [of the Serpent Gnostics].

Boryanabooks (2013) summarizes the situation:

The faction [of the early church] that became Catholicism confronted not only the Gnostics but endless other claimants within the Christian fold …. [W]hen Christianity became the Roman state religion Emperor Constantine … [gave that faction] the military power to physically crush their religious rivals. … The victorious faction … burned the Gnostics’ books and their churches, and sometimes the Gnostics themselves.

Schaff (1890-1907) draws upon Eusebius, among others, for the historical record regarding Constantine and subsequent emperors. Wikipedia’s (1 2) summaries of some of those “endless other claimants” range from the first official execution of a heretic in 385 A.D. to the last one in 1826. Swartz (1927) says that – thanks to persecution that was “almost as aggressive” as the Roman Empire’s persecution of the early Christians – by 600 A.D. “all serious opposition to the Roman Church lay effectively crushed.”

After that, it was largely a matter of wiping out pockets of heresy that would pop up from time to time – such as the Waldensians (c. 1200 A.D) – a movement begun, according to Wikipedia, by “a wealthy merchant who decided to give up all his worldly possessions and began to preach on the streets of Lyon,” whose followers “endured near annihilation.” (New Advent’s (n.d.) Catholic coverage of that genocide is far more muted.) The madness largely ended with the wars of religion (1522-1712 A.D.), which gradually established that the Catholic church had finally lost the power to torture and kill in order to maintain its political and theological dominance.

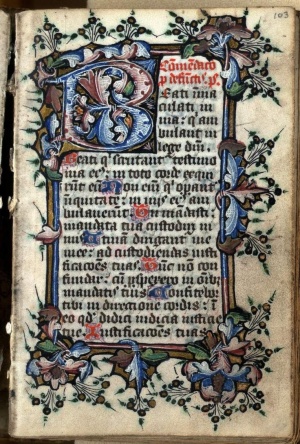

Image of the Shepherd of Hermas, from the Roman catacombs

Not surprisingly, these factors did not foster a repeat of the Old Testament pattern, where apocryphal works continued to emerge from the source religion’s culture until that culture was dispersed. Rather, as noted above, New Testament apocryphal sources were largely eliminated by around 400 A.D. Even so, a few early works now considered apocryphal continued to be treated, at times, as serious candidates for inclusion in the New Testament canon. Notably, Codex Alexandrinus (above, c. 400-440 A.D.) included 1 and 2 Clement; Codex Sinaiticus (c. 330-360 A.D.) included Shepherd of Hermas and Epistle of Barnabas; Codex Claromonanus (c. 550 A.D.) contained those last two plus Acts of Paul and Apocalypse of Peter; some ancient manuscripts treated 3 Corinthians and Didache as canonical; and numerous early English Bibles included the Epistle to the Laodiceans. (For other canons, see Wikipedia 1 2 and Davis, 2010.) The Clementine Vulgate (1592 A.D.) contained a number of works that were largely not seen in those earlier manuscripts, as does the present-day Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo canon.

Just as that handful of apocryphal works came close to acceptance, so also a handful of early Christian works that did ultimately become established were left out of various early canons. These antilegomena (from a Greek term used to denote “written texts whose authenticity or value is disputed”) have been listed toward the end of the New Testament at least since the time of the Vulgate (405 A.D.; see Council of Rome, 382 A.D.): everything after Philemon (except 1 Peter and 1 John) was suspect. According to Birner (2019, p. 13), Eusebius distinguished antilegomena (“disputed, but recognized [as canonical] by the majority”) from spurious books (i.e., not canonical, but not to be rejected altogether) (see Christian Cyclopedia, 2000).

A Speculative Psychohistory of Early Christianity

As indicated in the preceding paragraphs, assorted early Christian preachers, writers, and political figures entertained various ideas about putative scriptures that they created, favored, or criticized. Evidence and cold rationality certainly played a role in their debates and conclusions. But they also seem to have been influenced by mental preconceptions and emotional precommitments regarding a number of matters, ranging from political objectives to personal religious experience. In response to the dearth of ancient documentation on such matters, this section speculates about historical and psychological phases leading up to Athanasius’s final New Testament canon (367 A.D.).

- Documentation. Within a relatively short time after the crucifixion – say, 20 to 30 years – some of the first Christians were no doubt dismayed that the end of the world and the return of the conquering King had failed to occur promptly, as they had originally expected. Some of the older witnesses of Christ’s ministry had already died, disappeared, gone senile, or otherwise showed signs of forgetting or confusing important aspects of the story. Belief in Jesus gained only limited traction among the Jews who had encountered him firsthand: plainly, Judaism as a whole was not convinced, either in Palestine proper or in the cities abroad that Paul visited. Within the relatively small world of Judeans who had witnessed the phenomenon of Jesus, or among kids of the next generation who found the stories fascinating, a few had the skills, the motivation, and the means to collect information and to write it down. (Dartmouth Ancient Books Lab (2016) says that parchment was expensive. But Skeat (1995, contra Akin, 2016) says that, labor aside, papyrus was cheap.) There may have been some resistance to writing it down, even within the influence of a Jewish culture oriented toward written scriptures: Wheeler (2018, summarizing relevant pages in the Oxford Companion to the Bible) cites early writers who ostensibly encouraged oral rather than written transmission of the gospel – even as they, themselves, contributed to the written corpus. Mark may have been the only one within the proto-orthodox community who undertook such journalism in the early decades; he may have become the one who compiled multiple written and/or oral records into a single manuscript; or at least he was among the few whose relatively early work survived. It appears that the logic of Mark’s project became more compelling within the next few decades. We have three other presumed-authentic gospels that that community adopted; possibly others materialized as the number and quality of firsthand witnesses continued to decline, and as potential writers accumulated information and perspectives with which to supplement or revise Mark’s portrayal (see Mowry, 1944, p. 76). Presumably they were especially likely to do so as they detected a growing audience for such material. Possibly those three gospels did not start out in finalized form; possibly there were preliminary drafts, beefed up as readers shared their own recollections and reactions, and revised as the collective understanding of Jesus and of their religion evolved. Indeed, reasons for the brevity and the early dating of Mark’s gospel may be that, within the decades after its completion, he was dead, or stubborn, or intent upon keeping it simple or preserving its original clarity or making it available in an authoritative, final form sooner rather than later. Possibly he concluded that it all seemed to depend on him – that nobody else was doing it; that if he didn’t do it, maybe nobody ever would.

- Promotion. The first Christians didn’t want the story of Jesus to die – but it didn’t seem to be going very far. For those who believe that Acts 2:41 is historically accurate, the summary seems to be that, shortly after the crucifixion, on May 28 of the year 30 A.D., God gave the early church a huge shot in the arm with the miracle of Pentecost, when the disciples suddenly began preaching the gospel in the assorted languages of their Jewish audience. This amazed everyone and resulted in 3,000 conversions to Christ in one day (with another 2,000 added later). It is not clear why that had to be a one-time stunt, when there was an obvious ongoing need for it. Books of the New Testament (Acts, especially) report that the apostles performed many additional miracles. But then the apostles died; we are left to infer that God mostly withdrew for the next 2,000+ years – as far as we know at present, he withdrew forever; and presumably many of those who were briefly deceived about the realities of Christian life by such extraordinary events gradually dropped it, and went back to their former beliefs. By 49 A.D., there were apparently enough Jewish Christians fighting Jewish non-Christians, in and around the Roman synagogues, to prompt Emperor Claudius to tell them to get out of Rome. But the new faith was still just a Jewish sect. The New Testament essentially says that the first Christians waited more than 20 years, after the crucifixion, before they finally found a salesman who could really make something of their raw material. Fortified with at least an oral if not a written gospel, along with any other helpful documentation that he could find in the small and perhaps increasingly lukewarm Jerusalem bubble, Paul had what he needed to start purveying it to the Gentile masses. By roughly 54 A.D., he appears to have founded congregations at Ephesus, Corinth, Thessalonica, and elsewhere. This was not a matter of dropping a few seeds in the ground and moving on: it appears that he might devote months to nurse a new congregation to some degree of stability. In the big picture, Paul had to pull Christianity out of Judaism before it would be recognized by the larger Roman world. He was modeling an evangelistic faith, not only as an example to the folks back in Jerusalem, but also for his own second-order teachers and missionaries. This project did not work out well for him in physical terms: he was reportedly executed in Rome c. 64 A.D., apparently due to Nero’s blaming Christians for the Great Fire that year. Thanks primarily to Paul, the second half of the first century presumably saw rising demand for material to feed believers who were applying the gospel to their own myriad life contexts. Simple letters from Paul (first collected, perhaps, by the church at Ephesus – see Mowry, 1944; compare Price, 1997) and a few others were placed upon a pedestal as manifestations of God’s wisdom, applicable not just to the individuals and churches to whom they were written, but to all believers everywhere. Seeing the need – variously attempting merely to help out, to share the joy, or to capitalize upon an opportunity – random individuals started cranking out pseudepigrapha, generating excitement and zany ideas and more than a little confusion.

Medieval image of St. John and Marcion (c. 1050 A.D.)

- Quality Control. In the first half of the second century, the mood turned more conservative. There was no longer any question that the miracles of Jesus and the apostles had ceased to occur. It was also more obvious that it might be a long time before Jesus returned. Therefore, it became increasingly important to preserve the memory of how great the church used to be – and also to swat down those who would confuse or pollute that memory by carrying the Christian faith in undesirable directions. Notably, in 132-135 A.D., Jews of Judea rallied around the messianic Simon bar Kokhba in a rebellion against Rome. Jewish Christians had to decide which messiah they would follow. Wikipedia says that bar Kokhba’s forces persecuted and killed Jewish Christians who did not join the rebellion – but that the Roman victory was even worse for those who did: “Judea was heavily depopulated as a result of … [an estimated 580,000 Jews] being killed or expelled, and a significant number of captives were sold into slavery. … [T]he Hebrew language … disappeared from daily use.” This event surely put a lot of weight behind Paul’s desire to free Christianity from entanglement with circumcision and other aspects of Jewish religious life and practice that Gentiles would tend to find complicated and unappealing. Now Judaism itself was suspect; “Christianity [was] increasingly recognized as a separate or independent religion” (Dunn, 2006, p. 315). Shortly thereafter, Marcionism (c. 140 A.D.) became popular – in part, presumably, because it minimized links between Judaism and Christianity, notably by rejecting the Old Testament God of the Jews. Marcion also tapped into Christians’ concerns about corruption of their faith by cutting back sharply against possible exposure to pseudepigrapha – by accepting, that is, only the few New Testament books listed above. The numbers of Christians throughout the early centuries can only be estimated (e.g., Stark, 1996; Schor, 2009; Wilken, 2012, p. 65) – but in any case, each year, an increasing number (and, in later centuries, an increasing percentage) of believers were born into the faith, rather than being converted to it. These born Christians (and others who shared their priorities) presumably formed a relatively stable and influential conservative bloc within their congregations – one that had become disillusioned with flash-in-the-pan zeal, with apocalyptic fantasy, and apparently even with Christlike self-sacrifice, and had instead become more interested in establishing their religion as an institution that would endure to educate their children’s children in the stories and principles they held dear. (After writing this paragraph, I discovered Greenwald’s (1989) hypothesis that knowledge was consolidated in the second century. Greenwald’s article (1987, p. 244) doesn’t seem to anticipate the ideas suggested in this paragraph.)

- Explosive Growth. In the short term, the early conservatives lost. Counting from the time of the apostles, it would take more than three centuries for their vision of Christianity to become concretized in a state religion, officially endorsed and protected from persecution, and relatively immune to disruption by frauds and by the people they considered heretics. It is easy to imagine that vast numbers of citizens of the Roman Empire would decide to call themselves Christians in the 300s A.D., when that affiliation became safe, popular, and finally almost mandatory. What is harder to understand is how the paltry number of Christians as of 100 A.D. – less than 10,000 altogether, according to some of the estimates cited above – managed to reach that level of power. Obviously, their numbers grew exponentially – but why? If it had been simply that their gospel was undeniably fantastic, we would see that in today’s Christianity or, even if that magic got lost somehow along the way, at least we would hear specifics of what was so fantastic about it back then. That doesn’t seem to be the case. To the contrary, the horde of heresies springing out of a Christian foundation during those centuries suggests that a great many people were not, in fact, very contented with Christianity as they encountered it, and took it upon themselves to improve it. The better answer appears to be that Christianity grew so fast precisely because it was so open to innovation. As Sheeley (1998, p. 515) puts it, the New Testament apocrypha supported “an early Christianity of extraordinary diversity.” Just as a free market induces inventors to come up with new solutions to old problems as long as they can count on certain basics (e.g., protection from criminals), maybe a free religion has an advantage in attracting participants and fostering innovation, as long as it starts from a plausible connection with things that people want in their belief systems (e.g., forgiveness, love, a purpose in life, a sense of the divine, an endorsement of oneself as basically a good person). Like excessively restrictive bureaucrats in the economic realm, the religious conservatives understandably squelched the variant ideas of the early church as departures from a safe, orthodox faith – but perhaps, in doing so, they also squelched the thing that had made Christianity such a powerhouse, offering something for everyone. The numbers of Christians continued to grow, notwithstanding the fall of Rome, as the geopolitical reach of the church expanded into the Middle Ages. But the prioritization of control undermined those essentials of a dynamic religious marketplace: it made the church an ugly monolith that murdered people merely for their intellectually defensible differences of scriptural interpretation, and for psychospiritually persuasive differences of opinion and belief. Through such processes, what would become mainstream Christianity continued to stray from the message of Jesus. Centuries would pass until, leading up to the Reformation, the Christian public began to understand the extent of that departure. Eventually the church became steadily less of a thing that people wanted to get into, and more of a thing that they wanted to get out of. Meanwhile, as of 2023, it was not clear whether there ever was an original, lost core of Christlikeness that deserved a central presence in the world’s heart and, if so, whether the world would ever find and be open to it.

Selection Criteria for Books of the New Testament

Given the historical, cultural, theological, and other concerns stated or implied in the preceding sections of this post, one might pause at the questions posed by Peckham (2011, p. 215):

If the Bible consists merely of books selected based upon human whims and power structures, why should one accept it as trustworthy and authoritative today? Why adopt such texts instead of any others that might be popular or personally palatable? Indeed, why accept any writings as authoritative at all?

A page from the Vulgate

The discerning reader may detect that Peckham’s phrasing primes the pump in favor of a conclusion that God must ultimately have chosen the books of the New Testament, leaving it to the community of believers to catch up and adopt them. As noted in another post, this is blasphemy, insofar as it makes God responsible for an incredible history of horrendous acts that were supposedly required by a New Testament that Jesus, himself, seems to have shown no interest in creating. We want the canon, yes – but is there any evidence that God does?

One need not read far into the history and theology of the New Testament canon to detect indicia of its decidedly human (i.e., not divine) origins and outcome. Heaton (2023) identifies two rationales that various scholars have cited to explain how the New Testament was formed: either Athanasius in 367 A.D. simply codified what others had already decided, or the collection “was formed by the application of three or four or six criteria for canonicity.” The discussion of Athanasius (above) has already demonstrated that the first of those two rationales is not correct: Athanasius did not merely endorse biblical authorities’ prior determinations. The second rationale is illustrated by Becerra (2019, p. 780):

During the second through the fourth centuries, as early Christians sought to define and distinguish between authoritative and nonauthoritative texts, there were primarily three criteria by which canonicity was determined: apostolicity, orthodoxy, and widespread use.

Arguably the most important criterion for church leaders was a text’s apostolicity, meaning its authorship by or close connection with an apostle. … Hebrews, Revelation, 2–3 John, James, and Jude were slow to be formally accepted on a large scale owing to some doubts regarding their apostolic origins.

Another criterion was a text’s conformity with a tradition of fundamental Christian beliefs. … [That is, the text had to agree with established beliefs regarding such matters as the Trinity], the reality of the incarnation, suffering, and resurrection of Jesus, the creation and redemption of humankind, proper scriptural interpretation, and the rituals of the church. The texts known as the Gospel of Peter and Gospel of Thomas, to name two examples, were rejected on the grounds that their portrayal of Christ was incongruent with this inveterate tradition of orthodoxy.

Another criterion for canonicity was a text’s widespread and continuous usage, especially by respected Christian authorities and in the large metropolitan centers of the Roman Empire, such as Rome, Ephesus, Antioch, Alexandria, and Constantinople. The broad use of a text implied its value for determining matters of faith and practice on a large scale and thus its relevance to the church beyond specific regional locales. … [In this sense canonization is a recognition of] already-authoritative literary works.

In other words, books were most likely to be chosen if they appeared to have an apostolic connection, were popular, and agreed with what people already believed. Regarding the first of those criteria, it is interesting to consider that people supposedly believed the text of the New Testament when it said that the apostles had lots of disagreements and made lots of mistakes – and yet those same people were confident that the apostles’ mere proximity to a text would magically signal its divine inspiration. Becerra also implies that the antilegomena were accepted because almost everyone’s doubts about them dissipated – but that is not true, as indicated in a StackExchange answer:

[T]he Nestorian churches still leave Revelation out of their canon. … The Syriac Peshitta omits it, and the Council of Laodicia did not recognize it. As late as 850, the Eastern Church listed the book as disputed. They still do not read from Revelation regularly.

Closer to the mark, Farmer (2013, p. 6; archive) observes that the alleged criteria by which the church ultimately chose the books of the New Testament were “by and large ex post facto and do not reflect the actual decision-making process.” Contrary to the supposed claim of apostolicity, Farmer cites “scholarly consensus that … 1 & 2 Timothy and Titus are pseudonymous and were composed … [long after Paul’s death, presumably] by the first generation of Paul’s followers” (p. 8). Farmer characterizes Becerra’s criterion of “widespread use” as “an explicit attempt to … fashion the Church into a more unified whole, based on those elements which the greatest number of Christians can agree” (p. 9). In a similar vein, Carrier (2004) summarizes Metzger (1987) thus:

[The selection of the canon] was largely a cumulative, individual and happenstance event, guided by chance and prejudice more than objective and scholarly research ….

[S]ince there was nothing like a clearly-defined orthodoxy until the fourth century, there were in fact many simultaneous literary traditions. … [The Catholic church] simply preserved texts in its favor and destroyed (or let vanish) opposing documents. Hence, what we call “orthodoxy” is simply “the church that won.” …

Indeed, the current Catholic Bible is largely accepted as canonical from fatigue, i.e., the details were so ancient and convoluted that it was easier to simply accept an ancient and enduring tradition than to bother actually questioning its merit. …

[W]e know of some very early books that simply did not survive at all, and recently discovered are the very ancient fragments of others that we never knew existed, because [none of the surviving manuscripts] had even mentioned them.

Heaton (2023) contends persuasively that Athanasius played a novel role by going beyond merely issuing a preferred list, as scholars and others had done previously, to the point of wielding power to state a final determination (and departing in various regards from those earlier conclusions), to which the church as a whole would then submit. In short, the answer appears to be that no selection criteria were enforced consistently, nor was there any controlling prior consensus. Athanasius considered what others had advocated; he observed what was politically feasible; and he flip-flopped as necessary (with, in Heaton’s example, the Shepherd of Hermas) to choose a solution that, in his judgment, the church would accept. And that’s how we got the New Testament. Centuries later, as Wikipedia indicates, Luther would insist that the Bible is “the sole infallible source of authority for Christian faith and practice” – but he would not explain how the Protestant believer could know which books God intended for it to contain, apart from his own (which was ultimately Athanasius’s) somewhat arbitrary selection.

Original New Testament Manuscripts

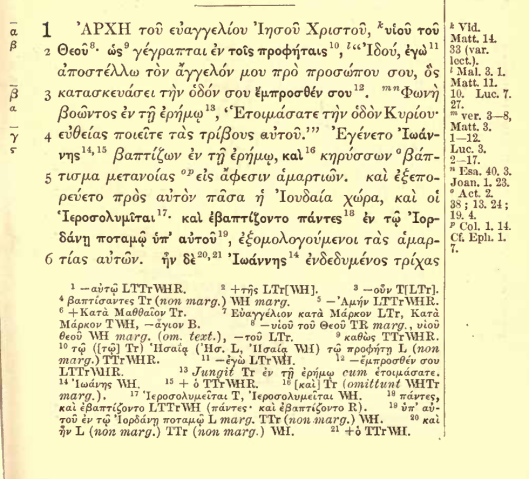

We have already seen that the text of the Hebrew Old Testament has emerged in various forms from preserved (original and translated) ancient manuscripts and from archeological sites (e.g., Qumran). Some of the same things are true of the New Testament, as detailed by Crossan (1992, pp. 425-426):

[S]cholars know, even if the laity does not, that the very Greek text of the New Testament on which any modern translation must be based is itself a reconstruction and the result, however executed, of a scholarly vote in a committee of experts …. The United Bible Societies’ third edition of The Greek New Testament [1975] grades disputed readings as A, B, C, or D …. “The letter A signifies that the text is virtually certain, while B indicates that there is some degree of doubt. The letter C means that there is a considerable degree of doubt whether the text or the apparatus contains the superior reading, while D shows that there is a very high degree of doubt ….” [T]hat scholarly reconstruction is made by collating manuscripts, all of which date, with one tiny and textually insignificant exception, from around 200 C.E. or after. Hence this warning from Helmut Koester [1989]: “The problems for the reconstruction of the textual history of the canonical Gospels … are immense. … Textual critics of classical texts know that the first century of their transmission is the period in which the most serious corruptions occur.” … And again, from François Bovon [1988]: “We must learn to consider the gospels of the New Testament canon, in the form in which they existed before 180 C.E., in the same light in which we consider the apocrypha. At this earlier time the gospels were what the apocrypha never ceased to be.”

That last remark is worth taking to heart. There is a real possibility that, within the first hundred years after Christ’s ministry, many committed followers of Jesus felt that beliefs we now consider standard were, in fact, heresies, comprising a disturbing departure from the dominant interpretation of Christ within their own belief communities. The early manuscripts destroyed or simply not copied by the Catholic church may have included some that would have introduced us to views that we have never heard, or that we may consider unsupported. Such possibilities encourage awareness, when the New Testament reader encounters things that do not add up – things that lost scriptures may have done a better job of explaining.

Discussing the most recent version (5th ed. (UBS5), revised 2018) of the Greek New Testament (known in Latin as Novum Testamentum Graece), Wikipedia quotes Aland (1995): “For over 250 years, New Testament apologists have argued that no textual variant affects key Christian doctrine.” That is certainly an interesting claim. The idea seems to be that the experts of the United Bible Societies did give grades of B, C, and D to numerous passages, indicating mild to extreme uncertainty as to what the original wording of those passages might have been – but by some miracle, not a single one of those passages had anything to do with any key Christian doctrines.

A page from a Greek New Testament (1887 A.D.)

That seems unlikely. What seems more likely is that this is what one would expect to hear from apologists – that is, people precommitted to “the intellectual defense of the truth of the Christian religion” (Grace Theological Seminary, 2021). Can an independent thinker trust such people to be honest about anything that could undermine their religion? I’d say no, they aren’t exactly famous for that sort of truthfulness.

Getting a little closer to the facts of the matter, Aland (as quoted by Wikipedia) goes on to say,

[I]n nearly two-thirds of the New Testament text, the seven editions of the Greek New Testament which we have reviewed [that is, the UBS version and six others] are in complete accord, with no differences other than in orthographical details (e.g., the spelling of names, etc.). Verses in which any one of the seven editions differs by a single word are not counted. This result is quite amazing, demonstrating a far greater agreement among the Greek texts of the New Testament during the past century than textual scholars would have suspected […]. In the Gospels, Acts, and Revelation the agreement is less ….

Wikipedia clarifies that wording somewhat. Of the 7,947 verses in the New Testament, almost 3,000 (i.e., 2,948, or 37%) contained differences in at least one (or perhaps two) significant words. Some of the worst percentages were in the most important books – specifically, the gospels, where the percentages of significantly varying verses were as follows: Matthew, 40%; Mark, 55%; Luke, 43%; and John, 48%. One-third (33%) of the verses in Acts contained significant variances, as did 47% of the verses in Revelation.

Aland is right: there is something “amazing” about that. What’s amazing is that half of the verses, in two of the four gospels, could contain significant textual discrepancies – and yet, again, miraculously, not a single “key Christian doctrine” would be affected.

Possibly the explanation for such nonsense is that the outcome is assumed, under the doctrine of verbal plenary preservation (VPP). That is, we know in advance that there couldn’t possibly be an adverse impact upon any Bible passage, because God wouldn’t allow it. According to Far Eastern Bible College (n.d.),

[VPP] means the whole of Scripture with all its words even to the jot and tittle is perfectly preserved by God without any loss of the original words, prophecies, promises, commandments, doctrines, and truths, not only in the words of salvation, but also the words of history, geography and science. Every book, every chapter, every verse, every word, every syllable, every letter is infallibly preserved by the Lord Himself to the last iota.

Wikipedia quotes various sources expressing a range of views – that VPP means that God perfectly preserved only “the original Hebrew and Greek manuscripts,” or also preserved the medieval Masoretic Hebrew text, or the even more recent selection of Greek manuscripts used for the King James (KJV, 1611) version of the Bible or, instead, that God’s textual insurance has continued right up to the present moment.

Such deeply troubled theories leave Wallace (2004) bemusedly speculating that “Scripture does not state how God has preserved the text. It could be in the majority of witnesses [i.e., ancient manuscripts], or it could be in a small handful of witnesses. In fact theologically one may wish to argue against the majority: usually it is the remnant, not the majority, that is right.” (See also MacLochlainn, 2015, favoring a belief or hope that the Holy Spirit resolves issues of divine inspiration in translation.)

It is pretty hard to believe – it is very unkind to our alleged Father to claim – that God was in the driver’s seat when the KJV became the dominant version in most English-speaking lands, misleading countless readers over a period of 400 years. Wikipedia mentions a handful of the KJV’s apparently incorrect passages, most notoriously the ending of Mark (16:9-20), with its bizarre claim of supernatural snake-handling powers for believers – a claim that has cost an unknown number of lives over the centuries. Other passages that may or may not have been in the original include those referring to Jesus sweating blood in the Garden of Gethsemane, the story of the woman taken in adultery, and an instruction that women should remain silent in churches. It is simply ridiculous to pretend that no textual discrepancy affects any key Christian doctrine when one of the contested passages listed in Wikipedia (1 John 5:7-8) contains an extraordinary reference to the Trinity.

Echoing earlier remarks (above) about ancient Hebrew scribes, Ehrman (2015) summarizes some of the issues surrounding the Greek New Testament manuscripts:

The vast majority of these hundreds of thousands of differences [among the full collection of New Testament manuscripts] are completely and utterly unimportant …. [But many of those differences] do affect how we interpret important passages of the books of the New Testament, and sometimes they affect significant teachings of the biblical authors. …

Having a few scraps from within a hundred years of when the New Testament was written does not give us what we’d really like to have: complete manuscripts from near the time the authors published their books. If our first reasonably complete copies of the New Testament do not appear until two or three centuries after the books were first put in circulation, that’s two or three hundred years of scribes copying and recopying, making mistakes, multiplying mistakes, changing the text in ways big and small before we have complete copies. We can’t compare these, our oldest surviving copies, with yet older ones to see where their mistakes are. There aren’t any older ones.

And the problems get worse. In later times, when we have an abundance of manuscripts, the copyists of the New Testament were trained scribes—usually monks in monasteries who copied manuscripts as a sacred duty. … In the earliest centuries, the vast majority of copyists of the New Testament books were not trained scribes. … The earlier we go in the history of copying these texts, the less skilled and attentive the scribes appear to have been. … If our earliest known copyists made tons of mistakes, how many mistakes were made by their predecessors, who produced the copies that they copied? We have no way of knowing.

That doesn’t mean, however, that we should give up all hope of ever discovering what the New Testament authors wrote. It simply means that there are some places, possibly a lot of places, where we will never know for sure.

For more on the dates of New Testament manuscripts, see Orsini and Clarysse (2012). For a general discussion of other problems addressed in this section, see Ahmad (2009).

Translation of the Bible into English

Once the scholars and authorities decided which books are in the canon, and which Greek and Hebrew manuscripts seemed to do the best job of capturing what those books originally said, all they had to do was to translate them into English, right?

Translations were theoretically possible as soon as the English language came into existence (c. 450-700 A.D.). Translation could have been made from Hebrew and Greek sources (above) or from the Vulgate (405 A.D.), which was itself an officially approved translation into the Latin vernacular.

Early translation would have been more compelling if there had been a substantial English market for it. King Alfred the Great (c. 880 A.D.) “clearly regarded the appearance of those who could read English but not Latin as a recent development” (Wormald, 1977, p. 103) and responded with a program (in which he may have personally participated as translator: Bately, 2009; see The Last Kingdom) that sought to translate a small number of important books into the contemporary (Old) English, including the book of Exodus (for its laws) (Wikipedia; see also partial Old English Bible translations predating Alfred). It appears, however, that English-language literacy remained an afterthought during Alfred’s time and, if anything, waned thereafter (Wormald, pp. 109-114). Calder (2015) asserts that literacy rates in Britain climbed from 7% to 16% later, between 1450 and 1550 A.D. Whether that was literacy in English specifically (as distinct from literacy in any language, including Latin) is unclear.

An early translation would also have needed approval from the church. Expressing a view repeated across multiple sites, My Catholic Source (n.d.) insists that the church hesitated to permit translations into the vernacular, “not to conceal scripture from people, but to protect scripture from corruption.” Yet numerous sources quote multiple popes for highly restrictive views, even in later centuries, that favored a flat prohibition of public access to scripture. For example:

[W]hat should we not fear if the Scriptures, translated into every vulgar tongue whatsoever, are freely handed on to be read by an inexperienced people who, for the most part, judge not with any skill but with a kind of rashness?… (Pope Pius VII, 1816 A.D.)

In similar spirit, an Encyclical of Pope Pius XII (1943, ¶ 16) says,

[We ought] to explain the original text which, having been written by the inspired author himself, has more authority and greater weight than any even [sic] the very best translation, whether ancient or modern; this can be done all the more easily and fruitfully, if to the knowledge of languages be joined a real skill in literary criticism of the same text.

The idea seems to be that you should not read translations; instead, our priests – all skilled in literary criticism – should explain the Greek and Hebrew sources to you. It is not clear why explanations of the original text require papal or priestly control, or why such control has been necessary at any point in the modern age of widespread literacy – or, indeed, why the Catholic church did not historically promote public literacy. Plainly, starting with the invention of the printing press (c. 1436 A.D.) and increasingly during the past few centuries, anything that a priest might say could instead have been provided in competing commentaries, written by people with excellent skills across multiple forms of biblical criticism (see Britannica, n.d.), and open to evaluation and critique by competent, disinterested reviewers whose remarks might have imposed some constraints on the church’s vast system of abuses and atrocities.

In the Middle Ages, the practical effect of Catholic restriction seems to have been severe. Wikipedia lists medieval laws against translations into the languages of common people. For instance, “At the synod of Béziers … in 1246 it was also decided that the laity should have no Latin and vernacular … theological books.” In England, the Arundel Constitution (1407 A.D.; see Hudson, 1975) banned translation of scripture into English, punishable as heresy (i.e., death by burning at the stake). After beng denied permission to print his English New Testament in England, William Tyndale tried in (but had to flee) Cologne, before finally publishing in Worms (1526 A.D.). That and Tyndale’s subsequent Old and New Testaments were banned and burned by Catholic authorities in England, where Tyndale himself was strangled and burned in 1536. Ironically, the Coverdale Bible meanwhile became the first officially approved English Bible (1535).